Note: This guide is a work in progress and may change at any time! We’ve done our best to cite our sources, but this page has not been professionally fact-checked.

This workshop was first facilitated for the Tech Equity Coalition in partnership with the ACLU of Washington in August 2020.

What do the recent Black Lives Matter protests have to do with the COVID-19 pandemic? They’ve both triggered a rising tide of surveillance—the use of “smart” technology to track people.

It’s easy to get lost in the news about the latest alarming developments. So we invite you to join the coveillance group for a guided workshop on the deeper principles of how surveillance technology works.

We’ll discuss two key technologies you might have passed by in downtown Seattle without even knowing it: automated license plate readers and fusion centers. Through a series of stories, we’ll show what happens “behind the scenes” to your personal information. Through group discussion, we’ll show how to tell apart what’s new and what’s not new about the way surveillance works today.

This workshop is a pilot session that will run for an hour, so please come prepared to give feedback. Thank you!

Overview and timing

Total: 65 mins

- Buffer (in this time, ask participants to name what they hope to learn from the workshop) — 5 min

- Intro, history, smart streetlights, TOC — 10 min

- ALPRs (brief overview) — 7 min

- Fusion center (brief overview) — 7 min

- Break out into two groups; one for ALPR and one for fusion center — 15 min

- Monologue — 5 min

- Discussion and exercise — 10 min

- Share out / closing session + request for feedback — 15 min

- ALPR group — 2 min

- Fusion center group — 2 min

- Quick takeaways — 5 min

- Big group discussion on interventions — 5 min

- Feedback — 5 min

Slides

Facilitator script

Please read the transcript below in tandem with the slides. Green italics denote a new section, [brackets] denote a new slide.

New & Old Snakes

[title slide]

Hello and welcome to today’s workshop, covering surveillance, protest and technology. Unfortunately, we couldn’t give an “in-person” tour, so think of this as a virtual one through time and space. We’ll be focusing on ALPRs and Fusion Centers with a chance to dig in at the end with breakout groups.

Feel free to add a more personal introduction to yourself and/or your organization and fellow facilitators.

[headlines]

With worrisome escalation across the nation against Black Lives Matter protests and increasing pandemic era surveillance, these are just a smattering of headlines that make us question what kind of dystopic hell we’ve been dropped into and how to make sense of it all.

[not a moment in time]

Borrowing from this quote from the StopLAPDSpying Coalition rings true—this is not a “moment in time, but a continuation of history.” We want to draw out the familiar and the new of this particular unspooling of history.

The first stop of our tour today is in San Diego.

[news headline – police used streetlights to investigate protests]

Let’s give a quick recap of what happened in San Diego.

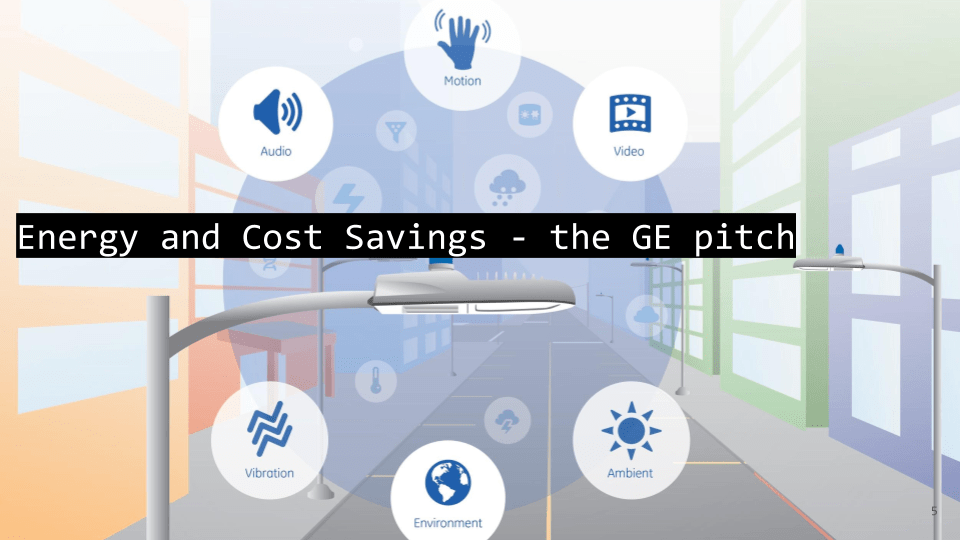

[GE diagram on their pitch]

In 2016, the city of San Diego installed energy-saving LEDs, cameras, and sensors – supposedly for sustainability purposes.

Well, only the LEDs contribute to sustainability. The cameras and sensors gather pedestrian and vehicle data and weather data – supposedly for city planning.

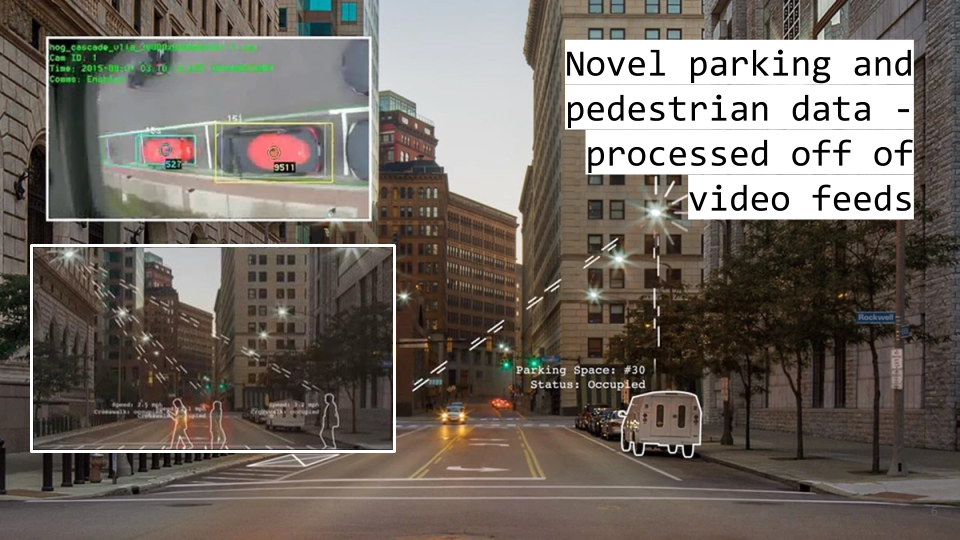

[Streetlight parking and pedestrian detection]

Computer vision on streetlight cameras give traffic data like parking spot detection and pedestrian analysis, which is data the city never had before. However, that means these cameras are recording public space 24/7 in high definition. So even though these smart streetlights were only supposed to grant access to SPDB in cases of serious crimes, that definition has slowly crept into minor crimes like vandalism.

San Diego police were using streetlight footage before the protests, but journalists have revealed that SPDB has been actively combing the footage to indict protestors for things like throwing objects or vandalizing buildings.

[“Man charged with pointing laser pointer”]

What we know so far is that the feds have gotten involved, charging two men connected to the protests. One of those men was arrested for shining a laser pointer at a helicopter that was monitoring the protests. Smart streetlight footage was gathered for his case.

[old snakes, new skin quote]

Even though all this sounds sci-fi and futuristic, this is actually a repeat of a lot of stories we’ve seen before.Whenever a “new innovation” in policing or carceral practices emerges, I think of this Frederick Douglas quote: “…you and I and all of us had better wait and see what new form this old monster will assume, in what new skin this old snake will come forth next”

He was speaking after the civil war, warning abolitionists that slavery would only be reborn in new forms.

[old snakes]

There’s power in naming racism and xenophobia, because they come cloaked in other forms. For example, racism in the name of protecting capital and property, and xenophobia in the name of identifying and casting others as state enemies. These snakes take form in white supremacy and abuses of power at all levels – personal, cultural and institutional.

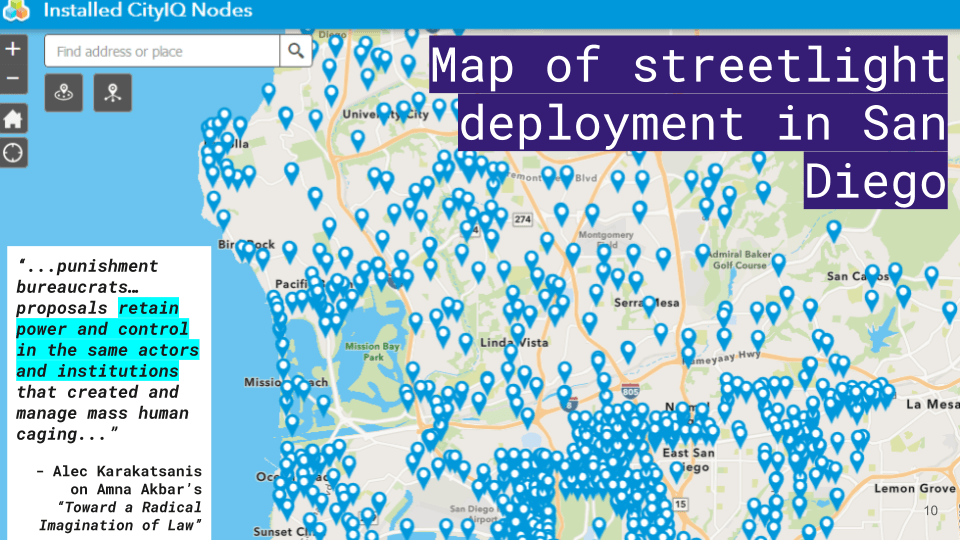

[Streetlight map]

The city paid for many of these lights with grants intended to “help local communities overcome poverty and the city justified its use in this context by putting the equipment in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods.” (source)

This attempt to “help communities overcome poverty” actually concentrated control in the same actors and institutions that reinforce racism and xenophobia, rather than in any transformative models of community power.

[new skin]

We can take a common “big data” trope – the 4 V’s of Volumen, Velocity, Variety and Veracity – and think about them in the context of surveillance. The power of big data comes from its ability to draw from as wide a pool as possible – dragnet info-gathering rather than targeted surveillance. From there, the use of data can give the veneer of objectivity.

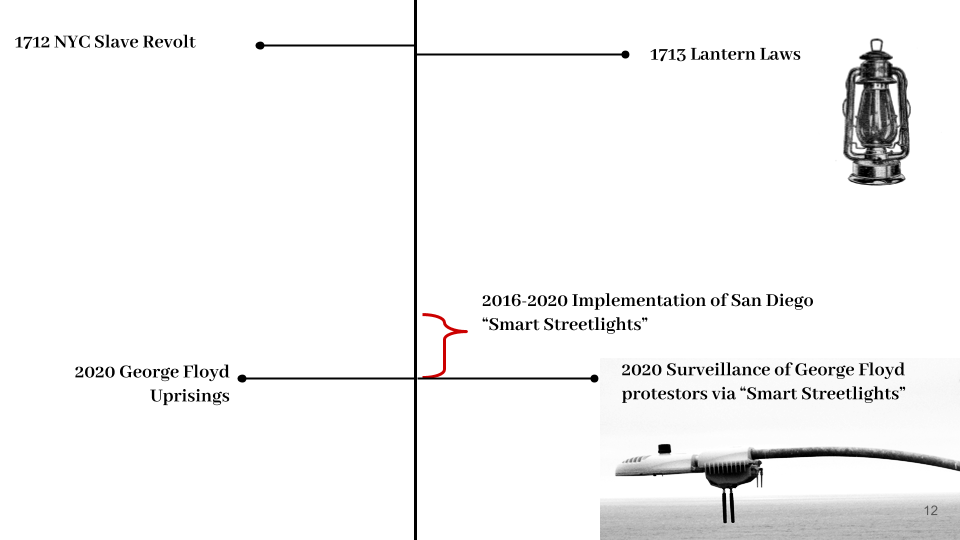

[timeline lantern and streetlights]

Well, to understand the context of smart streetlights, we want to revisit a different story about city lighting.

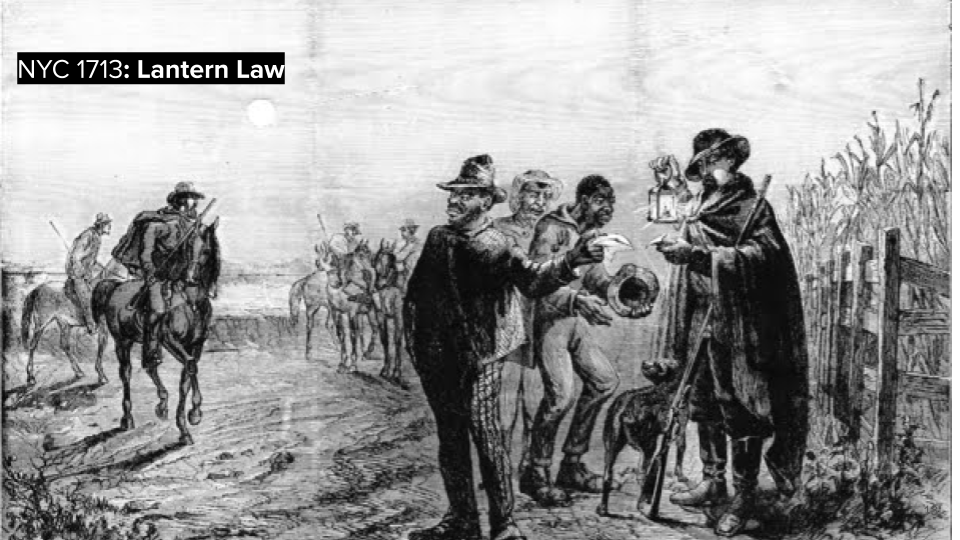

First let’s go to 1712, during the New York City Slave Revolt. As a part of The next year, as a part of crackdown in the city, the Common Council of the City of New York passed “A Law for Regulating Negro & Indian Slaves in the Night Time.”

[lantern law]

The law required all Black and indigenous people to illuminate themselves with a lantern after sunset, deputizing private citizens to bring in violators for punishment.

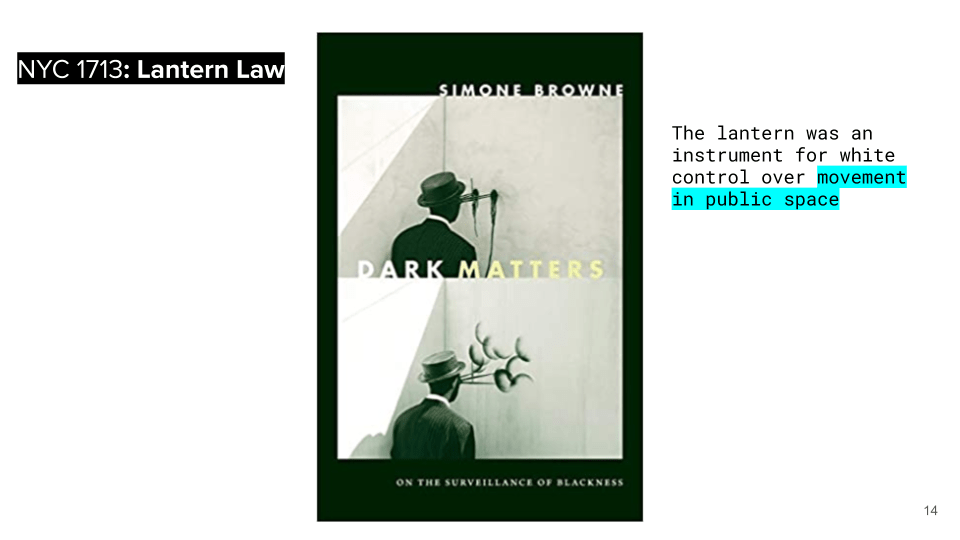

[Simone Browne’s Dark Matters]

Simone Browne in Dark Matters explains how the candle was an early, rudimentary piece of technology used as a form of control. What were they controlling? Movement through public space. The lantern allowed a “new” scale of encoded white supremacy – our “old” snake.”

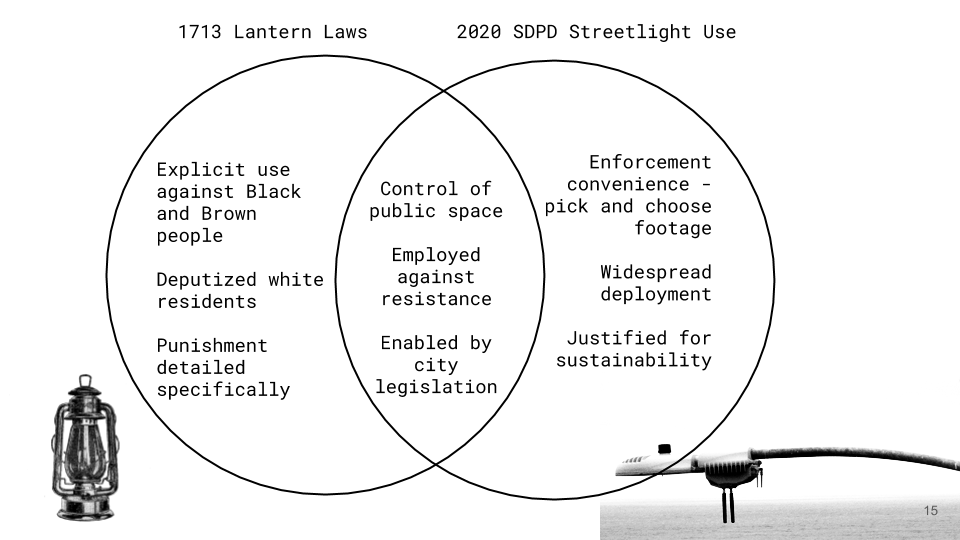

[lighting venn diagram]

Yes – the volume, or pervasiveness of these streetlights allowed the San Diego police to use camera footage 175 times to target whatever alleged crime – serious or not – they wanted. Which of course, extends to policing protests.

[timeline]

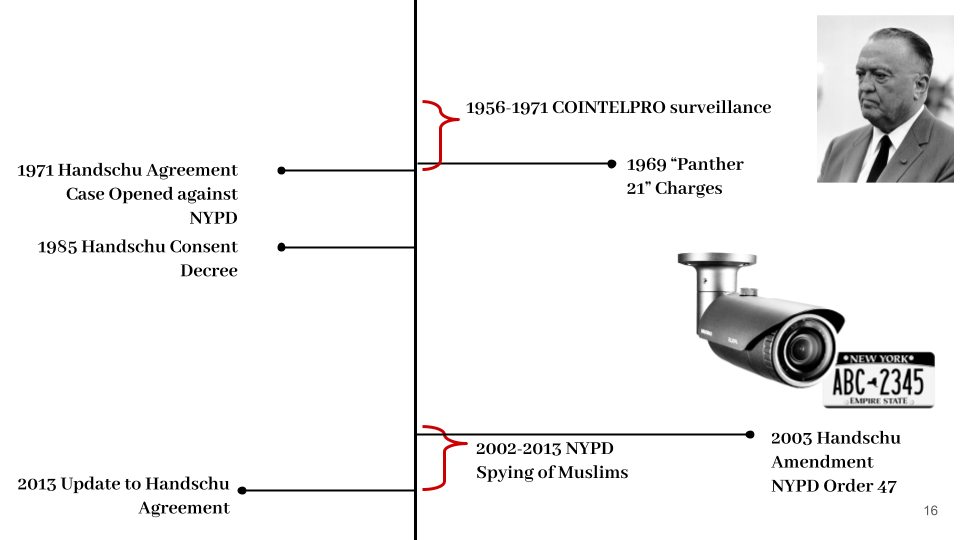

A more recent example of this old/new context of surveillance is the NYPD’s spying of Muslims. It combines the use of “new” surveillance tools like ALPRs with the “old” practice of domestic surveillance of social and political movements.

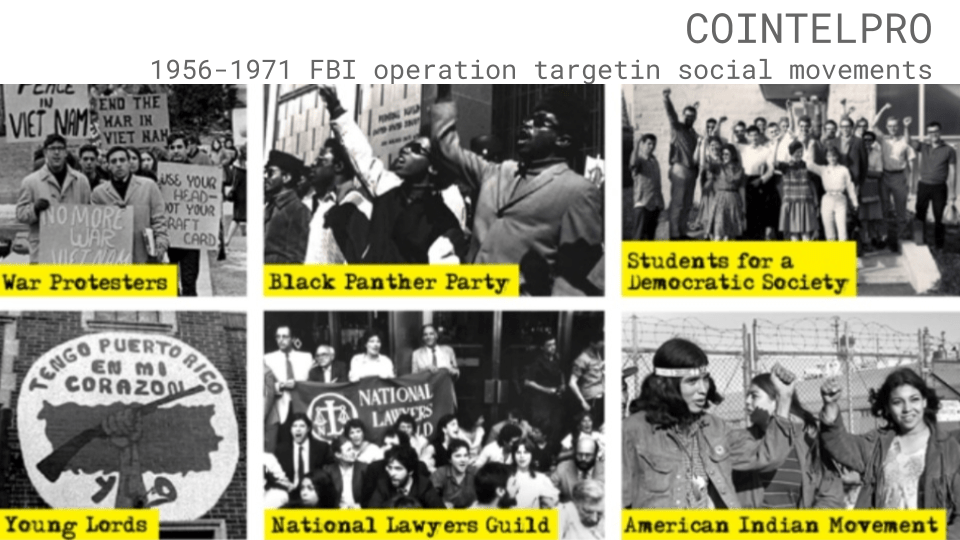

[COINTELPRO]

From 1956–1971, J Edgar Hoover ran the FBI program COINTELPRO to undermine social movements. Local police units that collaborated with this political spying were called “Red Squads.”

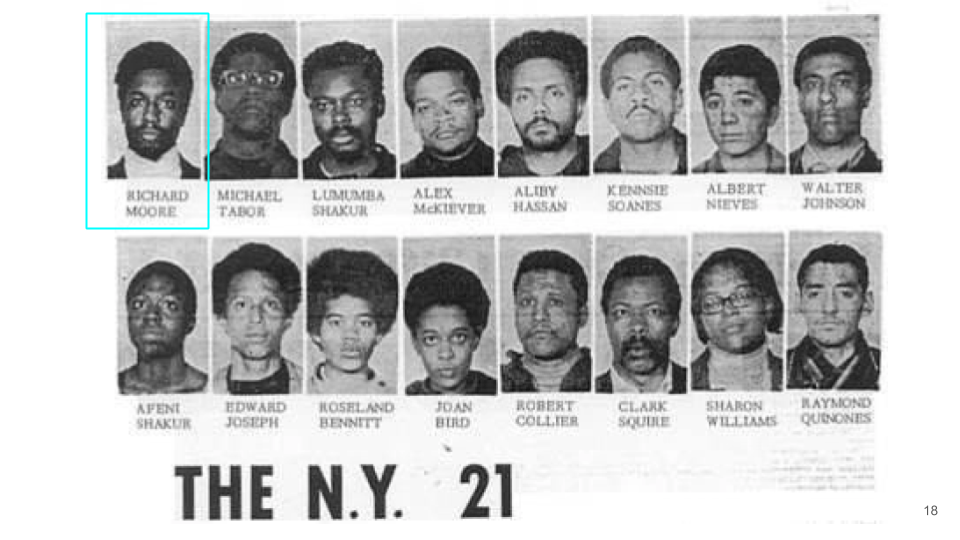

[Panther 21]

COINTELPRO targeted anti-war Vietnam protestors as well as civil rights movements. In 1969, the NYPD indicted the “Panther 21,” members from the Black Panther Party, on over a hundred of unfounded conspiracy charges as a result of COINTELPRO surveillance.

In the corner here is Richard Moore, known as Dhoruba bin-Whahad, who was targeted for this leadership role with the Panthers, explaining what happened next.

[45 sec clip]

The “Handschu Agreement,” established oversight limiting domestic spying by NYPD. It created a paper trail through record keeping and procedure, prohibiting spying on political and religious groups unless there was information tying them to a crime, and limited the share of information to other agencies.

[NYPD stop spying on me image]

These gains did not last long. After 9/11, NYPD removed those guidelines in the name of counterrorism, opening up a decade of unjustified surveillance of Muslim communities, including video surveillance, license plate recognition, community mapping, and infilitration.The ACLU, the NYCLU, and the CLEAR project filed suit against the NYPD in 2012, re-opening the Handschu case. This resulted in an update to Handschu Agreement that establishes greater oversight on NYPD spying.

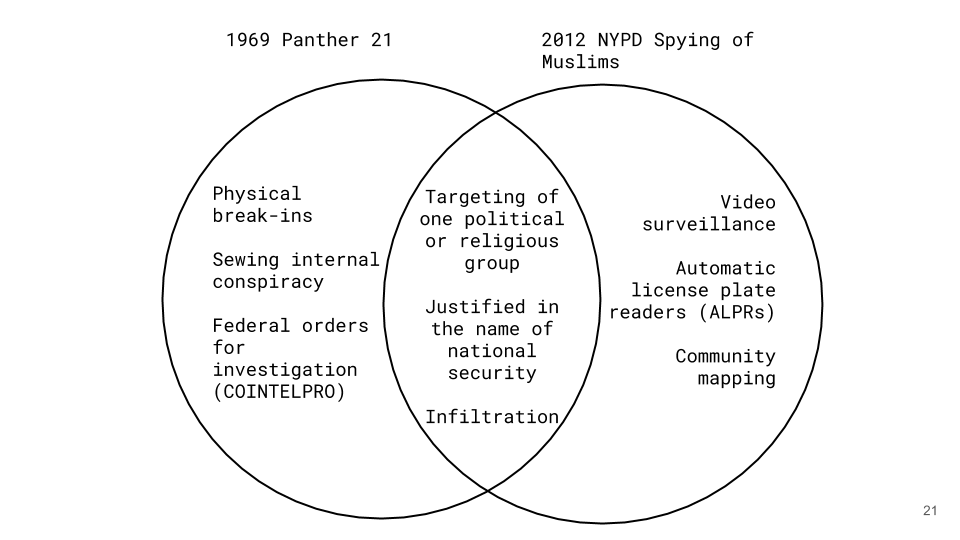

[venn diagram on NYC spying]

So what’s not new is this unwarranted political spying. What was new was the scale that NYPD was able to surveil so-called “ordinary” citizens – mounting license plate scanners on unmarked cars parked at mosques, for example.

First we’ll dive into the use of ALPR tools as an example of what is new and not new about smart city surveillance.

ALPRS (Automated License Plate Readers)

[what are ALPRs?]

See also – ALPR stop on our surveillance walking tour

What are automated license plate readers?

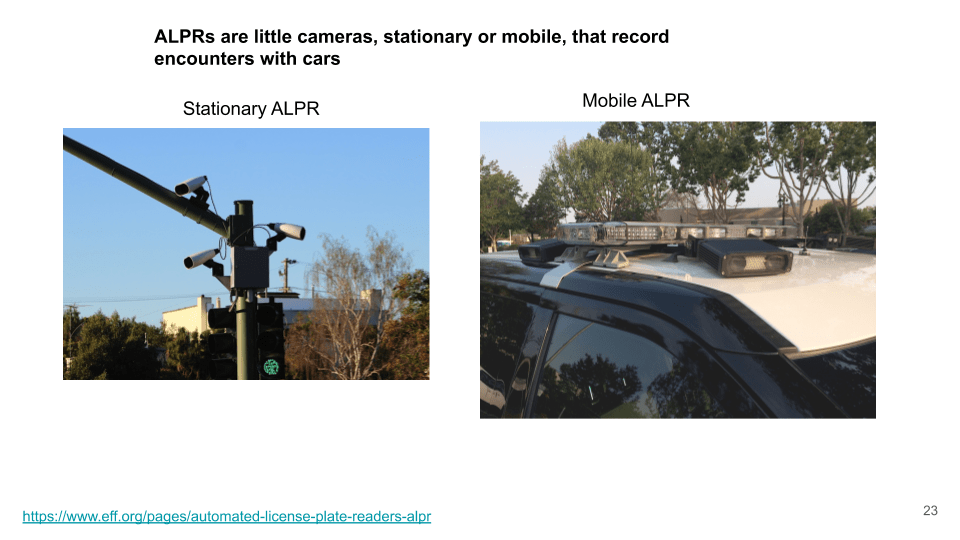

[a bunch of little cameras in situ]

See these little cameras mounted on highway overpasses, on poles above intersections and ramps, and on police patrol cars? These little cameras play a huge role in the surveillance ecosystem. Understanding what these things do will help you understand how all these other street-level surveillance technologies work as well as the problems with them.

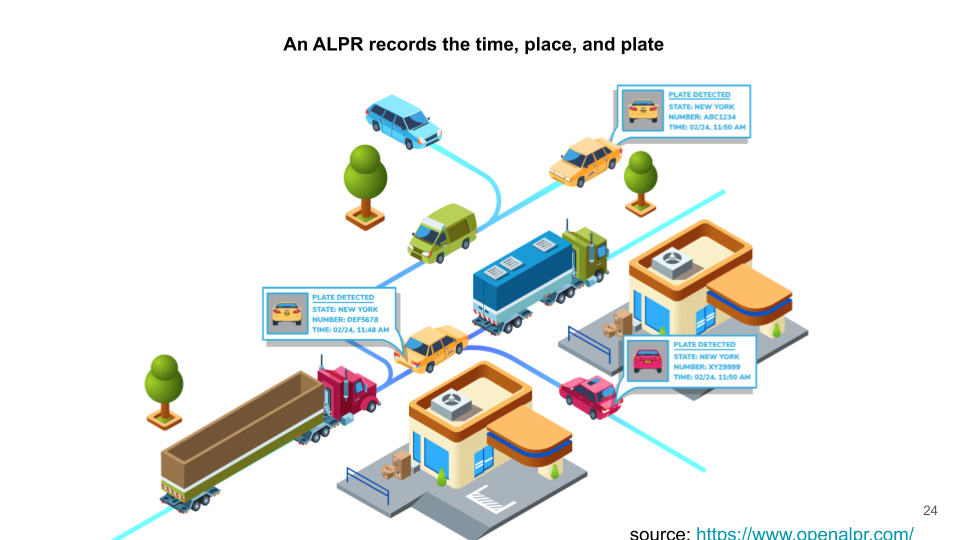

[diagram of what an ALPR does in a city]

Those cameras are meant to read the license plates of all passing cars, record the encounter, and store the information. When a car passes, it says, “Hey! I just saw a car with license plate ABC123 here, at 18 degrees lat 20 degrees long, from New York, at 11:50 AM on February 24.”

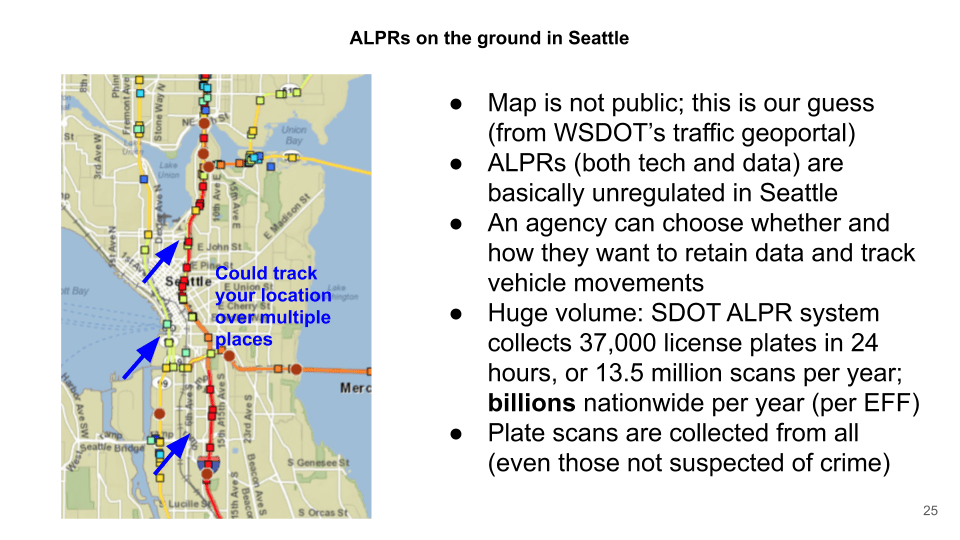

[ALPRs in Seattle — city map of ALPRs]

Here’s a map of potential ALPR locations in Seattle.

There’s not just one camera, but tens to thousands (depending on the city), often installed in dense areas like downtown areas or on highways. They are infrared so they typically run 24/7.

As you move around the city, you might be targeted multiple times by different license readers, creating a map of your movements.

Here are the basic facts to know about them.

[next build]

Note that maps of license plate reader locations are often not made public. This is partially due to the state not wanting people to know where they might incur speeding fines!

[next build]

Existing law in Seattle places no specific limits on the use of ALPR technology or data,

[next build]

meaning an agency can choose whether and how they want to retain data and track vehicle movements.

[next build]

There’s a huge volume of data. The Seattle Department of Transportation ALPR system collects 37,000 license plates in a 24-hour period—over 13.5 million scans over a full year.

[next build]

These drivers are not specifically suspected of any crime, which calls into question the scale and purpose of such data collection.

[Where does your personal information go?]

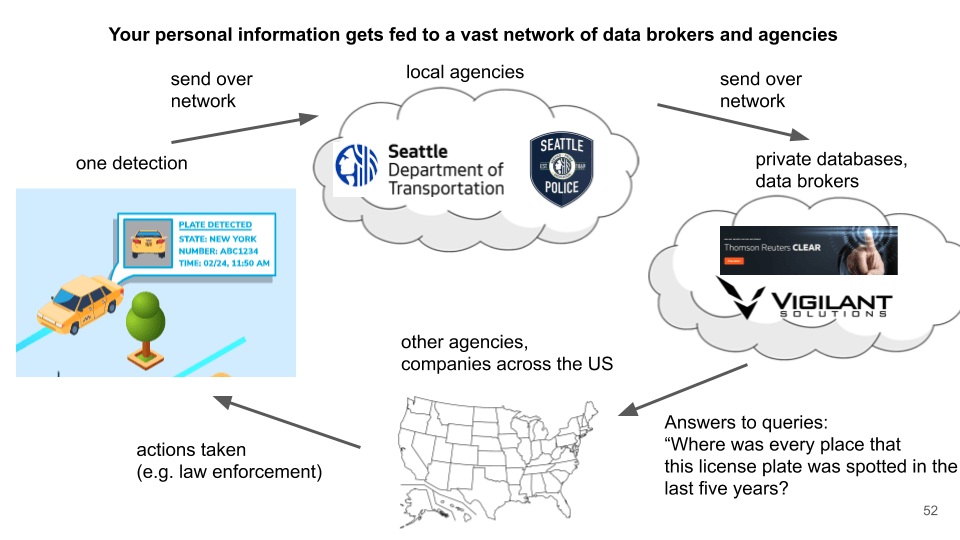

Where does your personal information (e.g. plate) go? Who sees it?

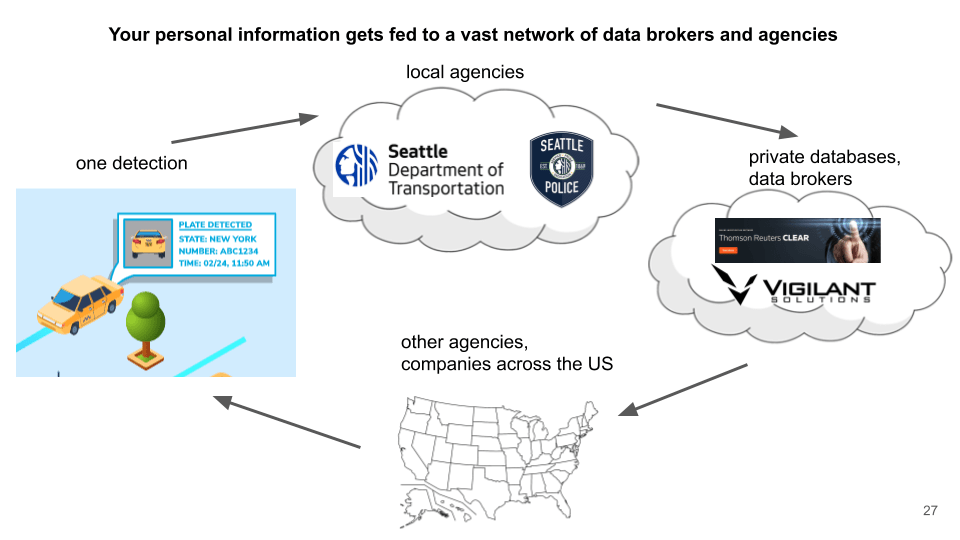

[Clouds]

When your plate is detected, the camera sends this record, over the network, to the public agency that owns the cameras, like a local department of transportation or police department. The info is probably stored “in the cloud.”

[next build]

Then, depending on the public agency, this one record might be sent to join a really big list of records, called a “database,” that usually a private company owns. This private company makes computer tools, or software, that help the users analyze the information.

[next build]

Then, this one record, inside the huge pool of information, is often shared with many other public agencies, some outside the state, some with different purposes from the original agency, like law enforcement instead of transit.

[next build]

Then, different agencies can run queries on the database, like “Where else has this car been today?” and “Who else was seen near this car?” These agencies can also get alerts if the license plate appears on a special list called a hotlist, for cars that have been stolen or owners who are wanted for arrest.

[next build]

These agencies can then take actions like sending workers to investigate a traffic jam, or sending officers out to intercept the car.

[smart cities]

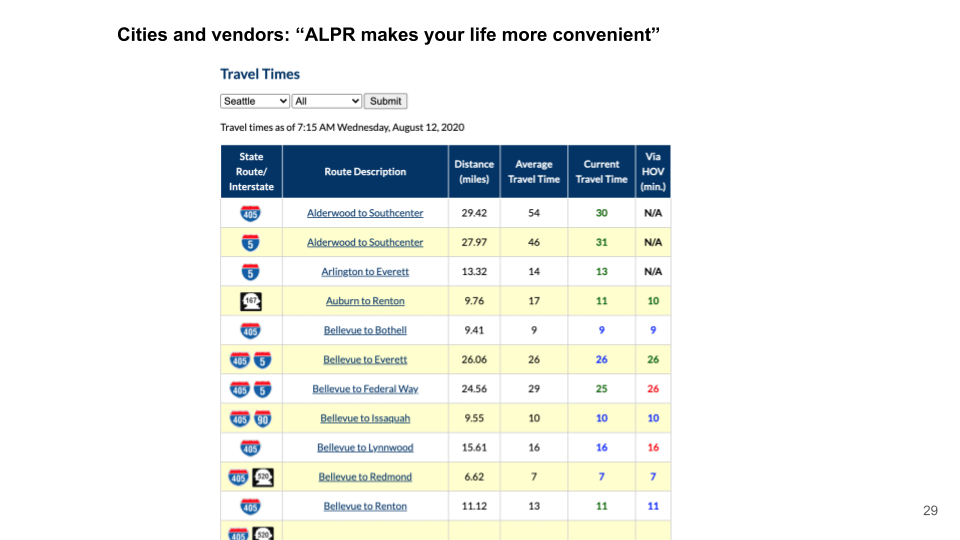

Things weren’t always this way—the ALPR was first deployed in 1984 in the UK, and since then, has supported an emerging narrative around “smart cities,” basically a high-density environment where people’s movements are tracked and stored at all times. What are the supposed benefits of “smart cities”?

The message from the city, or the vendors of the cameras, is: surveillance of public space makes everyone’s lives safer and more convenient.

[slide of traffic jam estimated time map]

If you ask a member of a city public affairs department, they’ll tell you those cameras are meant to make your life more convenient, for example, by giving you travel time information by measuring traffic.

[Vigilant slide]

If you ask a police officer, they’ll tell you those cameras are meant to make your life safer by helping officers capture fugitives and stolen cars.

While all credit must be given to the dedicated police officers and detectives whose tireless efforts solved this case, one can’t help but wonder if modern day advances in technology (namely License Plate Recognition or LPR) could have been used to identify potential suspects sooner – limiting the brutality and duration of these types of pattern crimes. After all, it was a license plate on a parking ticket that eventually led to Berkowitz’s capture.

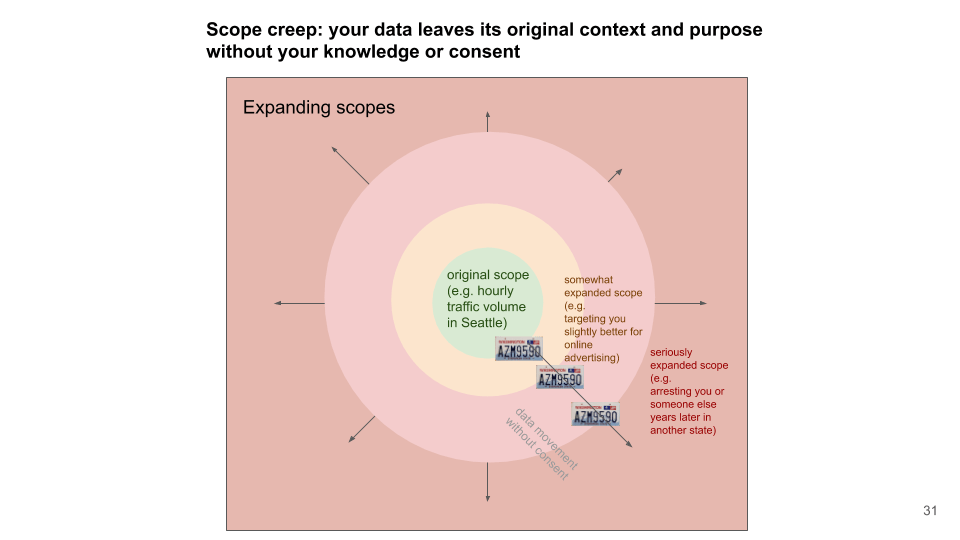

[Scope creep slide]

But scope creep of data is eroding civil liberties for us all. Here’s a diagram of how that works in general.

[next: original scope]

Your data starts in its original scope, for original purpose, such as helping measure hourly traffic volume in Seattle. Ideally it would stay here.

[next: expanded scope]

But then there are these expanded scopes. Like targeted advertising.

[next: data movement]

Through loose data retention policies, or agency requests, it experiences data movement out of scope, likely without your knowledge or consent. For example, if it becomes used weeks later to improve your targeted advertising based on where you were driving.

[next: seriously expanded scope]

Through several hops, it could move into a seriously expanded scope, just like in the smart streetlights example, where data used for “benign” smart city purposes was then used to target protesters, or if it ended up in the hands of a law enforcement agency in another state, who then used it as collateral evidence to arrest someone.

[next: wide scope background]

Each minor little “hop” might seem justified. Did you consent to any of these hops, or the final consequence? Where does the scope creep end? We don’t think anyone knows yet. But it’s crucial to fight it.

[NYT slide]

ALPRs are just one example of this general pattern. In our breakout group for ALPRs, we’ll examine a story about that, as reported by the New York Times in 2019.

The concentration of scope creep is best represented by fusion centers. I’ll turn that over to the other facilitator.

Fusion Centers

See also: Fusion Center walking tour stop

Who has heard of fusion centers before?

Note: include instructions for how to “raise hand” if you are conducting this remotely

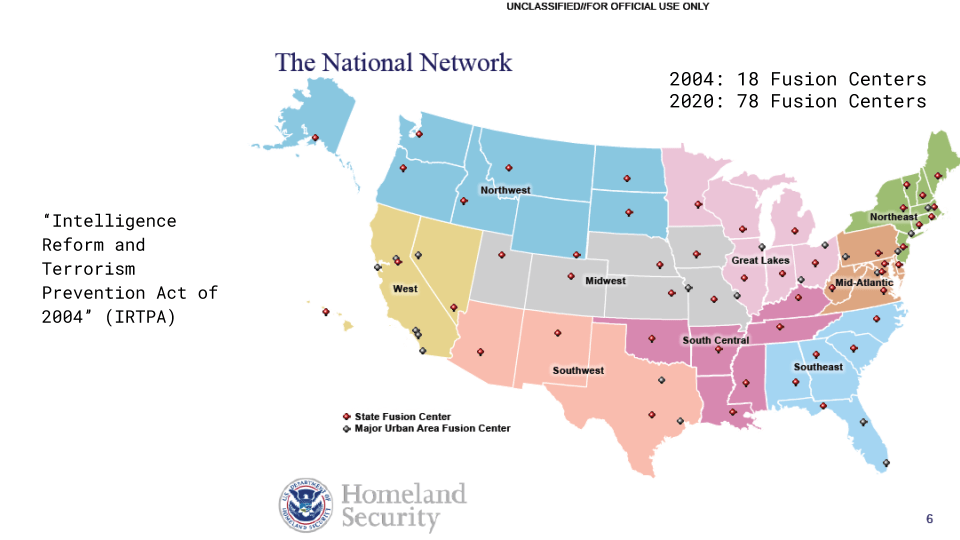

[map]

After 9/11, fusion centers were born with the “Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004” (IRTPA). With 18 at first, there are now 78 recognized centers. Fusion centers facilitated a national anti-terrorism strategy of intel sharing between local and national agencies as well as with private companies and the military.

[Washington State Fusion Center street]

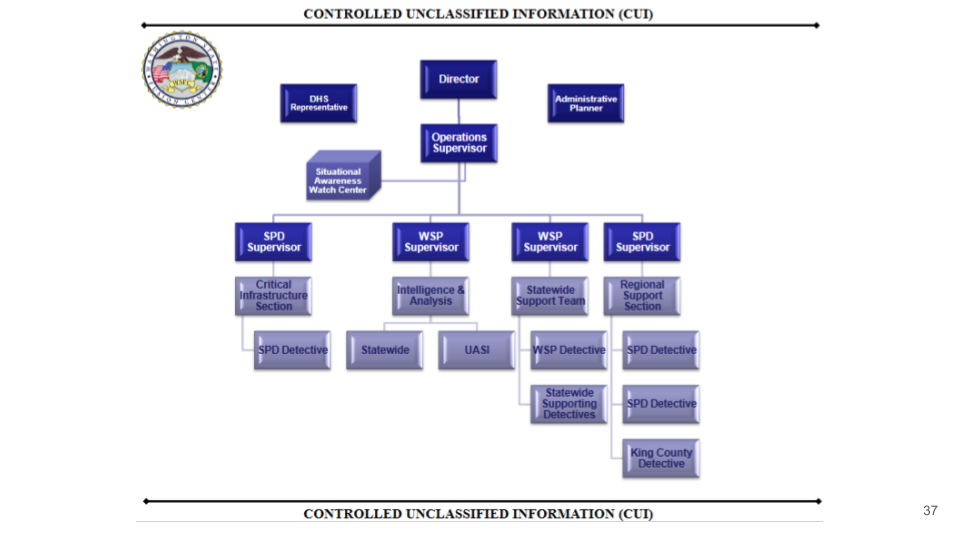

Seattle’s Washington State Fusion Center, is in the Abraham Lincoln Building, just downtown. These center employees are linked through the State Intelligence Network to every law enforcement agency in the state. A security corridor links them physically to the FBI’s Field Intelligence Group office and the Puget Sound Joint Terrorism Task Force.

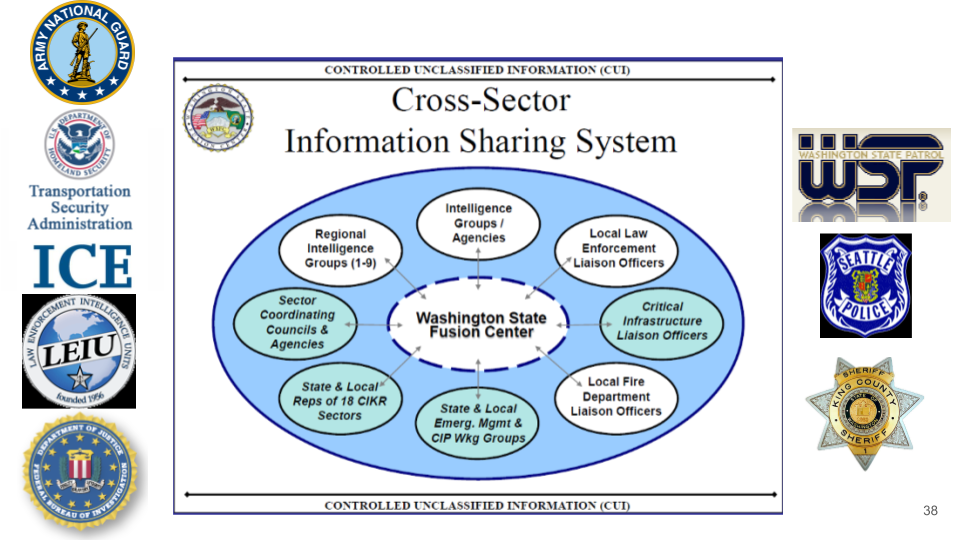

[sector diagram]

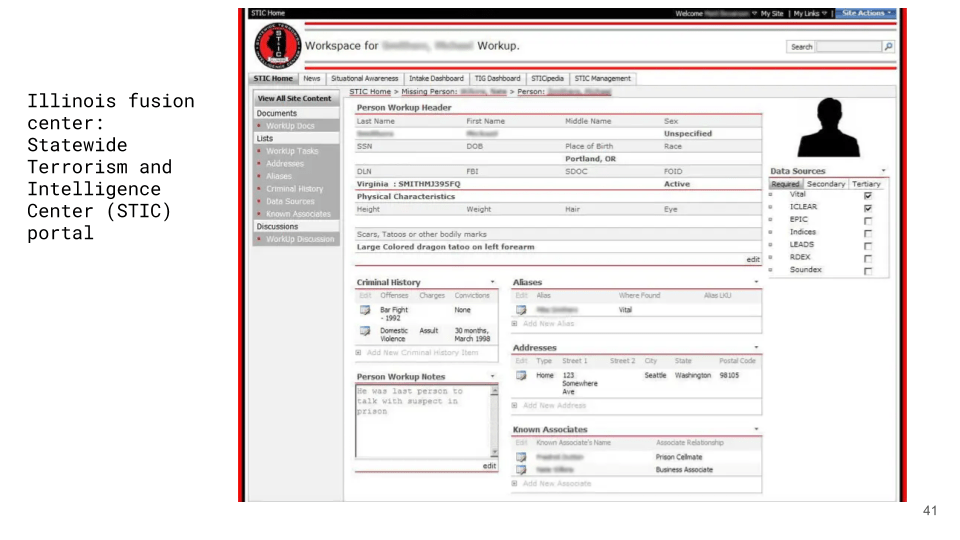

This marriage between federal agencies including the CIA, FBI, Homeland Security and other federal bureaus brings a level of national scrutiny to the local level, with individual reporting made possible through the Nationwide Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR) initiative.

Seattle’s fusion center seats a team of 15-30, with full time intelligence officers from the Seattle Police, County Sheriff, state investigators and analysts.

Fusion centers have access to the DHS’s Homeland Security Data network, and several FBI data portals.

[data sharing]

It might seem strange to have such a concentration of investigators in downtown Seattle, but fusion centers are also typically located in urban centers to put them in the center of multiple agencies that administer public safety needs, fire, emergency response, public health providers, and private sector security agencies. This gives them access to data that might be of interest to infrastructure related threats.

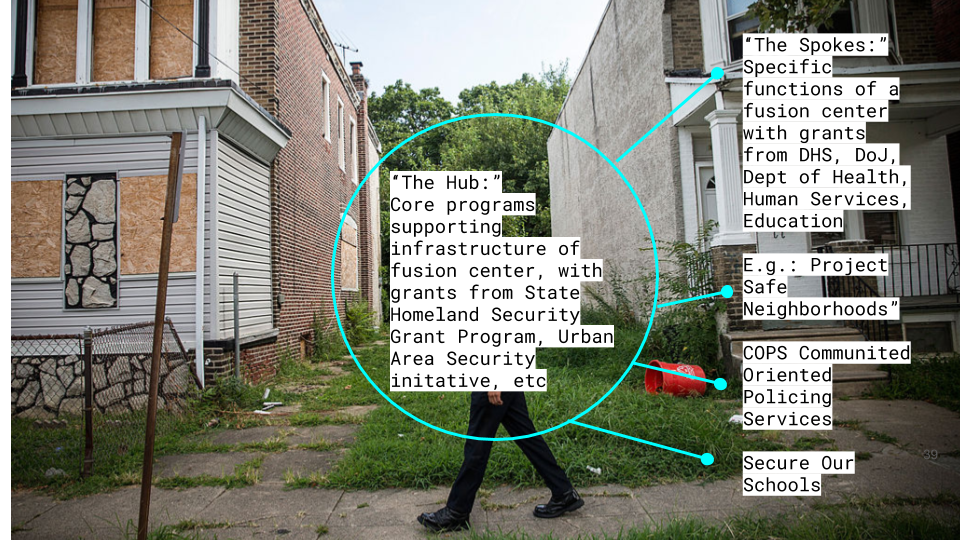

[funding]

Though the core “hub” of fusion centers come from similar grants, the specific programs of a fusion center are funded more individually, focusing on different domains including education, health, and neighborhoods in the name of public safety.

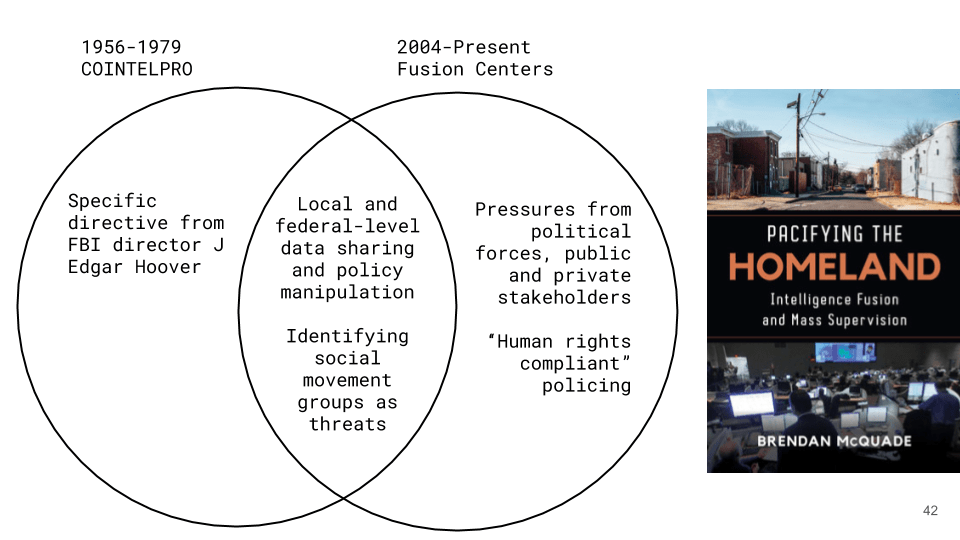

[decentralized COINTELPRO]

Multiple incidents of privacy violations and political monitoring are definite examples of concerns associated with fusion centers. But actually as Brendon McQuade argues in “Pacifying the Homeland: Intelligence Fusion and Mass Supervision” this confusing array of coordinating agencies makes it harder to expose political policing the same way as COINTELPRO in the Panther 21 / Handschu Case.

[venn diagram]

The success of the suit against NYPD on the spying of Muslims was the ability to recognize the “old” practices of targeting that violated constitutional rights in the same way as with the Panther 21. Fusion centers represent a new era of local, federal and private interests converging in a “harder to pinpoint” way. While fusing new tools of control for law enforcement like ALPR data, they also obscure the intentions and command chain related to practices that further racial injustice and violate human rights.

ALPR Breakout Group

This section begins a breakout group; this is not shown to the whole group.

[NYT slide]

Welcome to the ALPR breakout group! I’ll discuss a story, then we’ll discuss some questions about it together. At the end, we’ll report our findings back to the group, so please take notes if you can.

In this story, we’ll see how scope creep of data is eroding civil liberties for us all, and ALPRs are just one example of that. Can I get a volunteer to take notes?

[NYT ICE story photo of background from reporter’s blog]

All right. I’ll start by setting the scene for the story.

Here in Washington State, in 2017, people kept disappearing in Pacific County’s Mexican community.

Residents noticed how their neighbors, good citizens, some of whom they’d known for decades, would just vanish. Mothers of young daughters would be deported to Mexico with little notice, their families torn apart.

They knew that ICE, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, was somehow tracking down these people. But how? Was it a mole at the drivers’ license office? A spy in their community?

[Seattle Times headline]

Here’s one answer. There was widespread uproar when it came out in the “Seattle Times,” in 2018, that the state’s Department of Licensing (DOL) was feeding information to ICE on request: if an ICE employee emailed to ask about a target, a DOL employee would respond with whatever it had, such as their driver’s license application form. Wasn’t this already bad enough?

[ICE handshake]

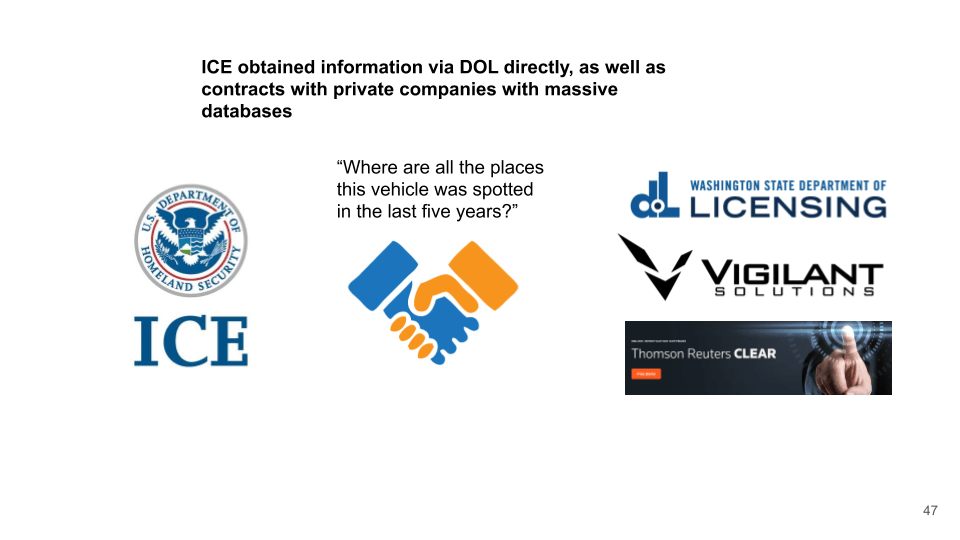

But the real answer was much more serious.

[next]

First, ICE already had direct access to the DOL’s database itself, so it could make its own queries without having to ask anyone. They made tens of thousands of searches in a software called DAPS (Driver and Plate Search) before the DOL cut off access last year (2018).

[next]

Second, even worse, it turns out that ICE obtained access to two huge piles of information.

The first is Vigilant Solutions’ database in Dec 2017. This is “the world’s largest privately run database of license-plate scans — more than five billion historic images captured continually and automatically, thousands per minute, by infrared devices, that is, ALPRs, attached to lampposts and police cars and repossession-agent vehicles across the United States.” Vigilant’s database lets ICE “see precisely when and where vehicles of interest have been spotted during the previous five years…. and upload 2,500-plate ‘hot lists’ that trigger immediate iPhone alerts whenever a target is scanned by a camera in the network.”

[next]

ICE also has access to a private database called CLEAR, created by Thomson Reuters (the news company).

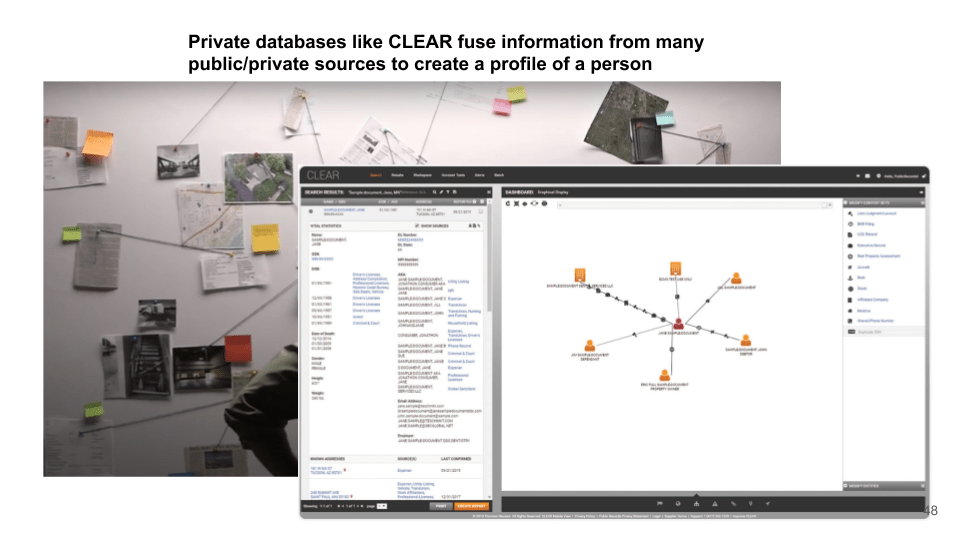

[conspiracy slide]

CLEAR enables a souped-up police network, just like the old cliche of investigators gathering tons of information on suspects and connecting it together by hand to find patterns and build a more complete profile of one person.

[next build]

But now… software lets us scale beyond what one person can do, as in this screenshot.

CLEAR gives ICE real-time access to address and name-change data from credit reports and to motor-vehicle registrations in 43 U.S. states, utility records, arrest records, and similar.

[The danger]

The real danger is that Vigilant and CLEAR’s databases aren’t restricted by protections on what data the government can collect or keep—because they aren’t government-owned.

As ACLU senior policy analyst Jay Stanley put it: “If ICE were to propose a system that would do what Vigilant does, there would be a huge privacy uproar and I don’t think Congress would approve it. But because it’s a private contract, they can sidestep that process.”

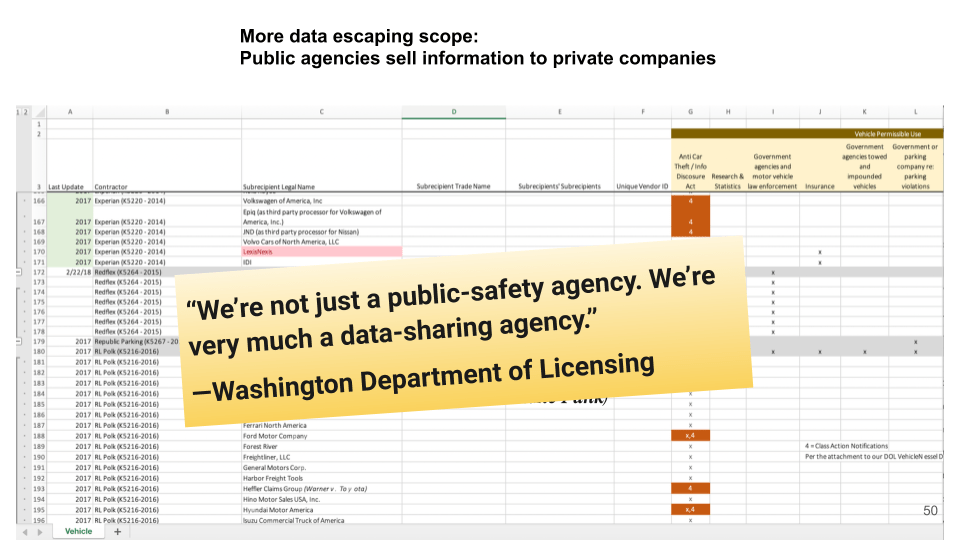

[“We’re not just a public-safety agency”]

Not only that, but public agencies sell information to private companies! As this spreadsheet shows, DOL sells its information to private data brokers, like Experian and LexisNexis, that resell information that end up in these Vigilant and Clear databases that ICE already has access to.

So cutting off access to ICE doesn’t effectively prevent them from having access to that database indirectly.

[next build]

As the DOL’s Brad Benfield said in May 2018, “We’re not just a public-safety agency. We’re very much a data-sharing agency.” Did you expect this when you registered for your vehicle?

“In 2017, D.O.L. earned about 26 million dollars selling driver and vehicle records to 19 principal data brokers, including Experian, LexisNexis and R.L. Polk — a group of companies that had its own relationships with some 34,500 ‘subrecipient’ brokers, including TransUnion, Acxiom and Thomson Reuters. ‘One of the things that we realized is that we’re not just a public-safety agency,’ D.O.L.’s Brad Benfield told a State Legislature committee in May 2018. ‘We’re very much a data-sharing agency.'”

[Oh, the places you’ll go!]

When it comes to plate data, law enforcement agencies share it directly.

The EFF found that of the 2.5 billion license plate scans from 2016-2017, law enforcement agencies are sharing data directly with ~160 other agencies, and adding to a “group pool” of data! All of this could happen across borders.

[Cloud slide]

In sum, as we saw earlier, information flows from you, [next] to local agencies–municipal or law enforcement–[next] to private databases and data brokers, to other agencies, that might then make decisions about you, as we’ll see in the following story.

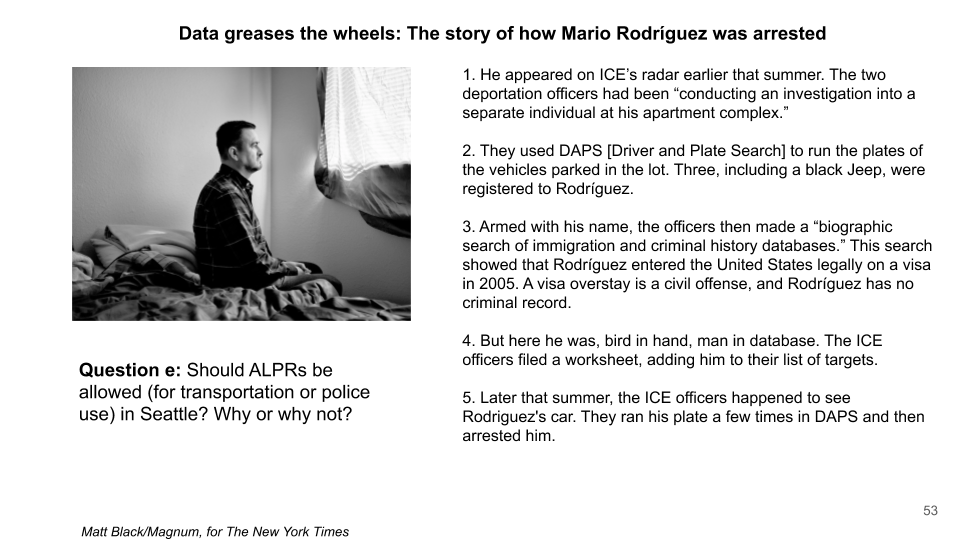

[NYT ICE story photo of Rodriguez]

Here’s the story of how that unfettered access enabled ICE to target Mario Rodriguez, a bilingual teaching aide who lives in Pacific County. As the NYT put it, “he matched none of ICE’s stated enforcement priorities, even under Trump.” There was no reason to target him. He is also gay, and has difficulty living in Mexico because of that.

[next] Here’s the first sentence.

Could we have volunteers to read out each sentence as it comes up?

1. He appeared on ICE’s radar earlier that summer. The two deportation officers had been “conducting an investigation into a separate individual at his apartment complex.”

[next]

2. They used DAPS [Driver and Plate Search] to run the plates of the vehicles parked in the lot. Three, including a black Jeep, were registered to Rodríguez.

[next]

3. Armed with his name, the officers then made a “biographic search of immigration and criminal history databases.” This search showed that Rodríguez entered the United States legally on a visa in 2005. A visa overstay is a civil offense, and Rodríguez has no criminal record.

[next]

4. But here he was, bird in hand, man in database. The ICE officers filed a worksheet, adding him to their list of targets.

[next]

5. Later that summer, the ICE officers happened to see Rodriguez’s car. They ran his plate a few times in DAPS and then arrested him.

Let’s just take a second to reflect on this story… What are people’s immediate reactions?

Begin the ALPR breakout group discussion.

Let’s break down this story based on some more general principles of surveillance. I’ll go over five discussion questions. Can someone volunteer to take notes?

DISCUSSION: Can you identify the personally-identifiable information Rodriguez had to hand over, that allowed the officers to track him?

Possible answers / discussion points:

- Vehicle registration -> license plate -> name

- Name, information, etc. -> get a visa to enter the US

- The better of a citizen you are, the easier you are to track (i.e. less above-board would be hard to track)

DISCUSSION: This is new: Can you identify all the ways that new tech made Rodriguez’s arrest possible?

Possible answers / discussion points:

- His car and plates would not have appeared in the database without a registration or an ALPR scan

- He was not targeted; they were investigating someone else, and DAPS lowered the friction to surveillance

- DAPS search gave them his name info from his plate info, which then enabled further searches

- Important point: the problem is not the ALPRs, the problem is the massive private databases gathered without oversight that fuse public/private information

DISCUSSION: This is not new:

In New York City, police officers drove unmarked vehicles equipped with license plate readers near local mosques as part of a massive program of suspicionless surveillance of the Muslim community. In the U.K., law enforcement agents installed over 200 cameras and license plate readers to target predominantly Muslim community suburbs of Birmingham. ALPR data obtained from the Oakland Police Department showed that police disproportionately deployed ALPR-mounted vehicles in low-income communities and communities of color.

Can you identify the ways that these kinds of stories perpetuate old patterns of surveillance/oppression?

Possible answers / discussion points:

- Dragnet information collection allows targeting of specific groups that have done nothing wrong, for creating a chilling effect on freedom of movement and association

- Currently, the use of ALPR technology in Seattle chills constitutionally protected activities because they can be used to target drivers who visit sensitive places such as centers of religious worship, protests, union halls, immigration clinics, or health centers. Whole communities can be targeted based on their religious, ethnic, or associational makeup, which is exactly what has happened in the United States and abroad.

DISCUSSION: How can this ALPR use impact you collectively—say, an innocent person who is not ever directly targeted by the state or do any crimes?

Possible answers / discussion points:

- bug in software (e.g. mis-recognized license plates) results in cops stopping innocent people who are said to be on the hotlist, with possibly violent/traumatizing tactics

- because so much of your information is collected/tracked without any need in the “dragnet,” it could be sold to predatory advertisers, or compromised by hackers or stalkers

- selective/retroactive enforcement: the more info that is collected, the more likely it is something can be considered a crime, or a pretext for one (e.g. empowering a racist officer)

DISCUSSION: Should we allow ALPR use in Seattle? Why or why not?

(Try to create discussion by questioning assumptions and asking for more detail )

(If all agree to get rid of ALPR: How could that change be made – what are the points of intervention within the system? If disagreement: Get people to talk with each other…)

Possible answers / discussion points:

- Public/private link

- Lack of oversight on private side

- Technology remains largely unregulated; limitations are just that of the technology

- Scale: one camera -> many scans; scans over Seattle per day, total scans over years

- Personalization: scanning one person over many cameras

- Dragnet surveillance

- What exactly the database contains and how that is connected/fused over space/time for a person, as well as over groups of people

- How new information is pushed/pulled to other entities (agencies) — and the magnitude of that

- Potential for scope creep and abuse

- Difference between, say, having an officer at every corner: memory. It does not forget, and can have wrong info stored

- If some tech is meant to have a purpose (like making life more convenient by measuring traffic), can achieve the same effect without it

- Possibility of software errors throughout the system, resulting in real (and real-time) consequences

Fusion Center Breakout Group

Who here knows who Phil Chinn is?

[“Phil Chinn”]

One of Seattle’s most famous cases involves the arrest of anti-war Port protestor Phil Chinn, a student at Evergreen State College who was arrested during an anti-war protest in May 2007, organized by a coalition of anti-war activists in the Olympia and Tacoma areas – Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Wobblies, and others. The activists had been infiltrated by an army intelligence officer who disseminated protestor information through the fusion center.

Chinn’s civil lawsuit of false arrest was settled with state patrol and Grays Harbor County and city of Aberdeen, with implications of a violation of First Amendment rights to free speech. Additionally, the direct involvement between military and local law enforcement, enabled through the intel-sharing of the Fusion Center, violated the Posse Comitatus Act.

How do fusion center operations relate to current protests? Can we mount similar defenses today?

[Occupy protest]

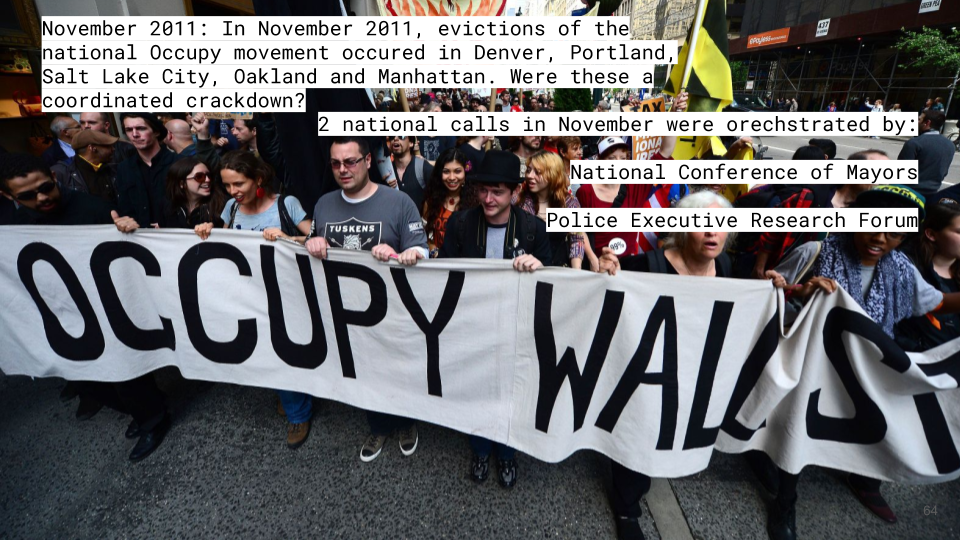

In November 2011, evictions of the national Occupy movement occurred in Denver, Portland, Salt Lake City, Oakland and Manhattan. Were these a coordinated crackdown?

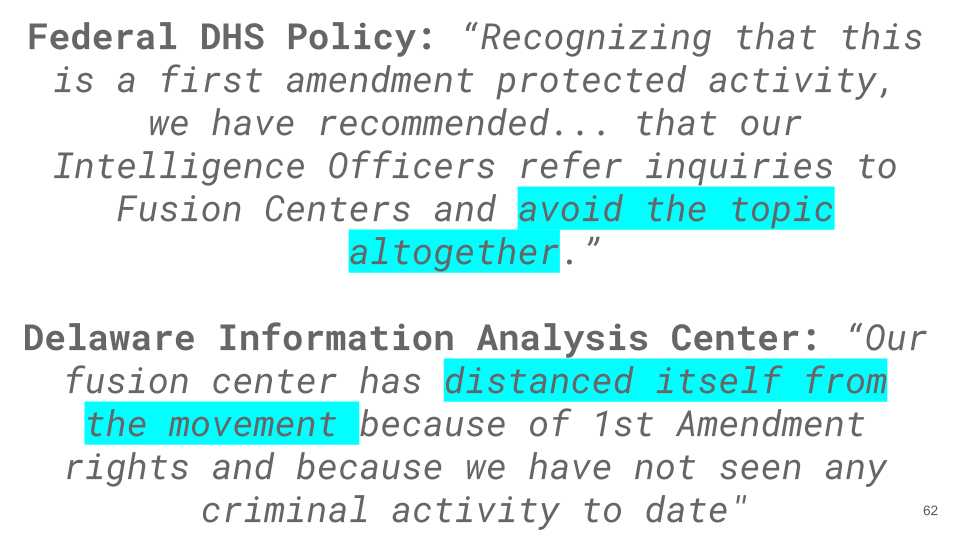

[DHS]

DHS’s official policies at the federal level and several fusion center responses suggested actually a policy of washing their hands of Occupy involvement.

[AZ]

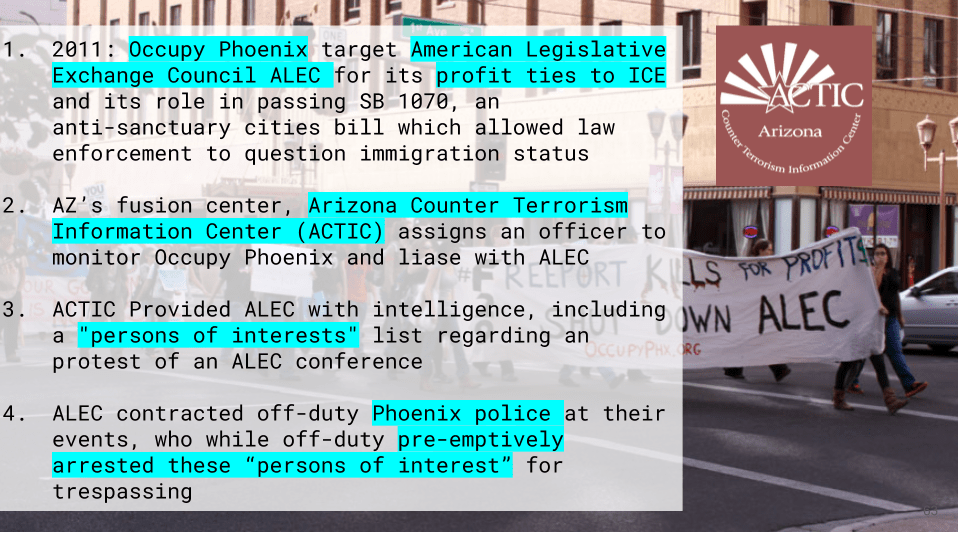

Then we have Arizona’s response to the Occupy movement. When Occupy Phoenix targeted the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) for its profit ties to ICE and its role in passing a bill that allowed law enforcement to racially profile latinx drivers, Arizona’s fusion center assigns an officer to monitor Occupy Phoenix and liase with ALEC. ACTIC Provided ALEC with intelligence, including a “persons of interests” list regarding an protest of an ALEC conference who were later targeted with arrests.

What explains the coordinated response? The common factor comes from the fusion center mandates that require private sector involvement.

[Occupy 2]

The November of the crackdowns, two national conference calls were organized – but by private entities, the National Conference of Mayors and the Police Executive Research Forum. Of course – these are private orgs of public officials.

[GTWO]

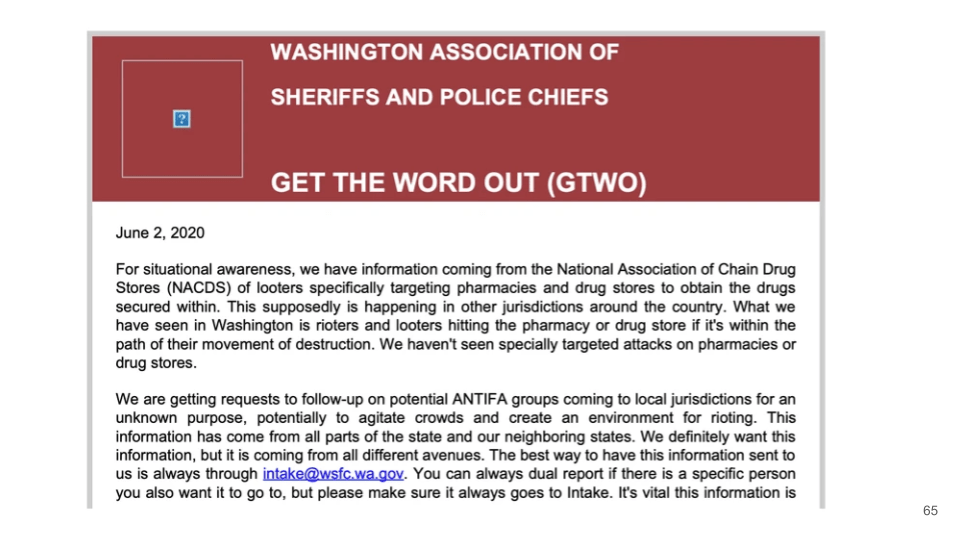

There’s a similar level of private sector involvement in today’s protest. Here we have a “Get the Word Out” memo distributed in the wake of the George Floyd uprisings, perpetuating the disproven “outside agitators narrative. This memo was disseminated through the Washington State Fusion Center.

Can someone mention who they were tipped off by? The National Drugstore Chain Association.

[Obama in Camden]

In 2015, after BLM protests spread in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s death, President Obama traveled to Camden to present the results of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. In Camden, Obama congratulated Camden’s lowered crime rates as a result of community policing programs and use of intelligence. Extensive neighborhood monitoring services and surveillance streams all feed back to the Camden “fusion center.”

As Minneapolis attempts to disband their police, mentions of Camden’s model have resurfaced. Camden’s police force disbanded in 2013 after reeling from hard economic decline.. This new “reformed” department, Camden County Police, opened a fusion center, the Real Time Tactical Operations Intelligence Center. Camden is a true surveillance city, with cameras, ShotSpotter gunshot detectors, automated license plate readers, and a mobile observation tower. Community policing interactions become intelligence gathering exercises. All of these data streams flow into Camden’s “fusion center” producing “predictive” analytics to direct police to blocks of interest. In the long term, the economic recovery plan for Camden manifested in corporate tax abatements to entice corporate interests along with police pacification.

[Obama Chicago]

A foil to Camden is what happened in Chicago, when Obama traveled to the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) in October 2015. Grassroots organizations shut down the the gathering, releasing the Counter-CAPS report, rejecting this model of policing. These orgs stand in contrast to BLM movement moderates had taken elements from this task force and launched Campaign Zero, who put out the “8 Can’t Wait” Platform. Earlier in March of that year, this same group had won a reparations bill compensating the 110 Black men tortured by Chicago Police, with .5M in damages, counseling, services and public school curriculum.

Surveillance is presented as an alternative model to incarceration and traditional policing. It’s being implemented – purposely or not – in tandem with the goal of improving city infrastructure. “Pacification theory” is a framework that describes our current industrial-security complex as a systematic war strategy with the intent of reinforcing class and the accumulation of wealth. The focus on protecting, controlling and upgrading a city’s infrastructure and property has clearly had the effect of disrupting and incarcerating its marginalized residents.

Q: Fusion Center funding models require private sector involvement. What do you think is the impact of private sector stakeholder interests in fusion center activity?

Q: How do you think smart city tech changes fusion centers?

Q: With ~⅓ of funding from federal homeland security grants, the rest is largely state funded and run. This means if you know one fusion center… you know one fusion center. What stakeholders do you think are involved in Washington?

Discuss: Microsoft funding of the National Fusion Center Association

Discuss: What are tools we have against such a large federal, local, and private conglomerates?

Possible answers:

- Do its strengths also contain its weaknesses? Discuss the fractured / rival chain of command

- Transparency calls and privacy concerns – do they work? Discuss the reformation of the Washington State Fusion Center

- Camden’s fusion center was created after its new police force. Could an effective intervention be warding against their creation and against disguised forms of new policing?

Conclusion

All right, let’s go over some general takeaways from what we just discussed.

[principles of smart tech]

What we learned from ALPRs, we can distill into some general principles of how surveillance, or “smart,” tech works. That is:

- It gathers personal information 24/7.

- This information is then associated with some unique identifier like a face or license number.

- Then this information is pooled with all the other information gathered–across the country, across many years, by different agencies—to build a profile on a person, to understand connections between groups of people, and to predict people’s actions.

- Based on this information, different private or public agencies make decisions about a person.

[problems with smart tech]

We can also distill our discussion into some general problems with surveillance, or “smart” tech. That is:

- New technologies are largely unregulated

- New technologies are gathering far more information than they need to — in terms of time, granularity, different senses

- There’s very little public transparency or oversight of these technologies–the limitations are usually that of the technology itself.

- The real danger is in the fusion of data in huge private databases with no oversight

- Can then be used to track people and their associations very granularly, often used by govt agencies specifically to target vulnerable groups

[next] Just remember the story of ICE and its reliance on private databases like CLEAR and Vigilant.

[generally effective interventions]

Finally, all hope is not lost. We can come up with some generally effective interventions to scope creep and infringement on civil liberties. For example:

- Pass laws restricting tech use

- Pass laws restricting data collecting, selling, sharing, and retention, especially to private companies / data brokers

- Demand public oversight/audits of proposed systems

- Refuse the tech

- Refuse to build it

- Adopt effective low-tech alternative

- Do participatory co-design to find real community needs, rather than top-down imposition (“no one asked for this”)

Solicit feedback from attendees.

Give contact info for your organization.

References

ALPR sources (accessed August 2020)

- NYT ICE surveillance article, mentions plate databases

- Seattle-specific

- ALPR SSO doc rebuttal + citations on p41 to previous cases of ALPR abuse

- http://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/Tech/Privacy/License%20Plate%20Readers_Final%20SIR.pdf — For SDOT

- https://www.seattle.gov/police-manual/title-16—patrol-operations/16170—automatic-license-plate-readers

- https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/Tech/Privacy/SPD%20ALPR%20(Patrol)%20-%20Final%20SIR.pdf — For SPD

- Police cameras busy snapping license plates (Seattle Times)

- https://www.seattle.gov/police-manual/title-16—patrol-operations/16170—automatic-license-plate-readers (Seattle policy)

- ALPR SSO doc rebuttal + citations on p41 to previous cases of ALPR abuse

- James Bridle’s article on ANPRS (ALPR in UK)

- EFF heatmap of movements in Oakland

- STOP ALPR page

- Verge article

- Clear/Learn/Vigilant

- https://corpwatch.org/article/us-government-using-vigilant-solutions-surveillance-cameras-and-database-track-migrants

- https://www.thomsonreuters.com/en/press-releases/2017/june/thomson-reuters-brings-vigilant-license-plate-recognition-data-to-clear-investigation-platform.html

- CLEAR, in their own words https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/products/clear-investigation-software?CID=TRSite

- Important EFF sources on ALPR datasets’ scale and sharing

Fusion center sources

- “Pacifying the Homeland: Intelligence Fusion and Mass Supervision” (Brendan McQuade)

- (Other sources to be added)

Feedback form

Here’s a sample feedback form on Google Forms: link.

If you’d like to make a separate form for your organization, write to us at team at (our domain) and we can share the Google Form with you.