Note: this guide is a work in progress and may change at any time! We’ve done our best to cite our sources, but this page has not been professionally fact-checked.

This workshop was first run as part of two pilot workshops with the Tech Equity Coalition, in partnership with the ACLU of Washington, in October 2019. A zine based on this work was included at the CtrlZ.AI zine fair and the HOT MESS digital exhibition in 2020.

Introduction

In this tour of downtown Seattle, we’ll practice spotting some of the layers of the “smart” city that are hidden in plain sight, collecting and storing data about our lives, as well as the kinds of thinking that justify their existence. Each surveillance technology in our field guide includes the following categories to help you “spot” surveillance technology in the wild: Address, Appearance, What it does, How the tech works, Social importance, Discussion and finally, References.

Tour route

This is the route we will be taking on the walking tour. Click on each stop to pop up its location, and feel free to explore it on Google Maps, e.g. with Street View. The route spans 1.3 miles. Below, we outline each of the surveillance tools/sites listed above.

Surveillance cameras

Address: Practically everywhere, but the above example is at 523 Union St.

Appearance: Poles, ledges, overhangs, rooftops. They are often spotted watching parking lots, doors, banks, intersections, and government buildings. Indoors, they are typically spotted on roofs and near cash registers.

What it does: The camera has a memory. It can record video or other data and add it to a store of records over all time. The camera can be controlled remotely: it can swivel, zoom, or change height.

How the tech works: Camera recordings can be analyzed for patterns and shared with other entities, both private (your neighbors) and public (the local police).

It might be connected to a network (via Internet or radio frequency), which lets it send video to anywhere, receive instructions from anywhere, and lets other people, who might be anywhere, watch the video stream.

Discussion

- What are other ways to question the need to have cameras, or surveillance, at all? What sort of society would we build around this way of life?

- What are your individual or communal experiences of “light shining more brightly on some than others”?

- What if each camera were replaced by a person? How would that change how you feel?

References

- Street-level surveillance overview (EFF)

- Video surveillance system overview (ACLU)

- What’s wrong with public video surveillance? (ACLU)

Amazon Go

Address: 2131 7th Ave

Appearance: Looks like it could be any other convenience store… but it’s not! Inside, you must scan an app to enter, and there are no cashiers.

What it does: Amazon Go tracks your movement using overhead cameras to determine your browsing habits.

How the tech works: Amazon can use your purchases to know more about you using patterns. For example, if you buy Hanukkah decorations, they might know you’re Jewish. Or certain foods might be correlated with certain health issues. They can combine your in-store purchases with your online Amazon purchases for even more predicting power.

What is Amazon doing with their knowledge about you? There’s no oversight or transparency. Your data could be sold to third parties without your consent.

Discussion

- What are the societal effects of targeting ads based on [race, gender]?

- When you go into Amazon Go, what do you imagine you are consenting to? How does this differ from the reality? How could this be changed?

References

- Facial recognition used at a convenience store in Seattle (another story)

- How much is your data worth? “No cash needed at this cafe. Students pay the tab with their personal data.”

Automated license plate reader

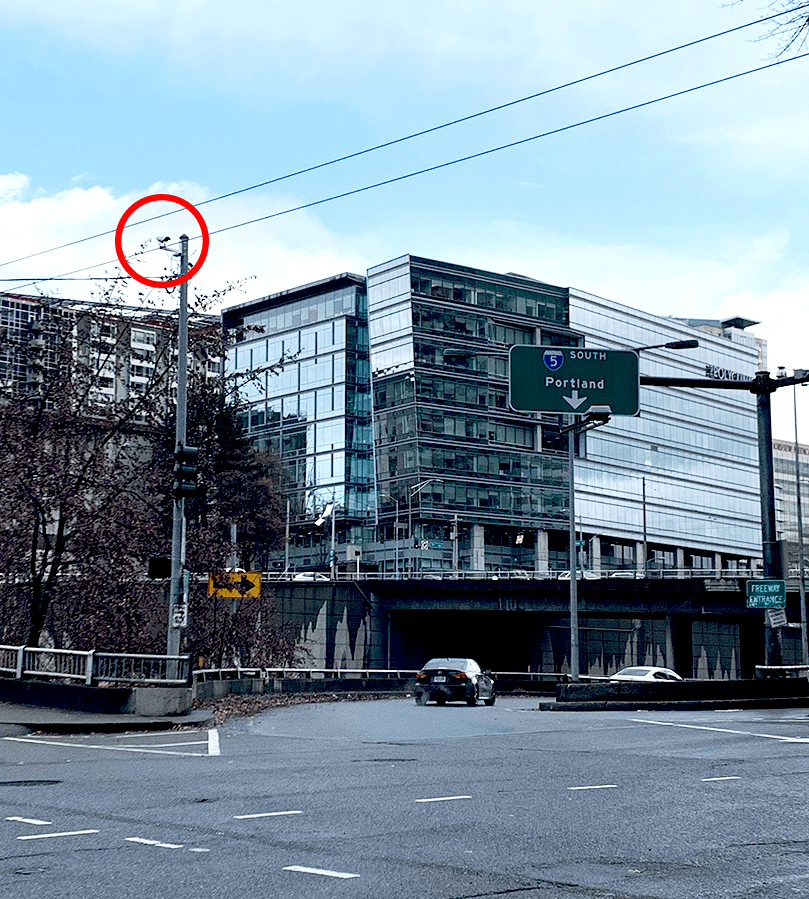

Address: 699 Spring Street

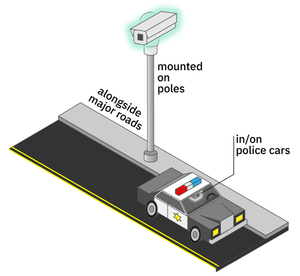

Appearance: An automated license plate reader (ALPR) is a little camera that is either mounted to a pole (stationary) in high-traffic locations or the top of a police car (mobile) (Fig. 2.).

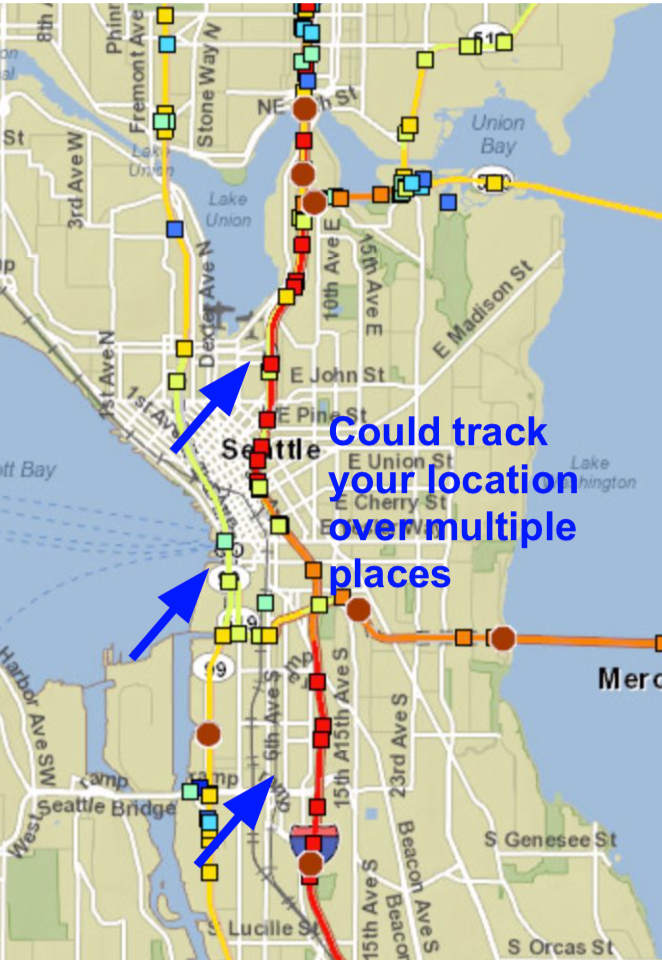

What it does: An ALPR photographs the license plate of every car that passes by and records the time and place of the encounter, as well as the plate number (Fig. 3.), and sends the information to a central storing place (called a database). Based on the information from an ALPR (e.g. “plate number ABC1234 detected at the intersection of Pike and Pine at 1:20 PM”), and the type of ALPR, a particular city agency may take an action.

There are three main kinds of ALPRs in Seattle. Stationary ones (type #1), owned by the Dept. of Transportation, are used for traffic purposes, to estimate travel time. Mobile ones, owned by the Seattle Police Dept., are used for parking enforcement (type #2) or law enforcement (type #3), to ping a police officer directly when a “wanted” license plate is spotted. These three kinds of ALPRs have different data retention periods; police ALPR data can be stored for up to 90 days, whereas other ALPR data is (supposedly) deleted immediately. In Seattle, the Seattle Department of Transportation has at least 99 stationary ALPRs deployed, and the Seattle Police Department has 19 vehicles with mounted ALPRs.

How to spot: ALPRs are usually mounted up high near high-traffic areas, like highways, downtown areas, interstates, and bridges. Maps of stationary ones are difficult to find because cities don’t want drivers knowing where they might be issued speeding tickets.

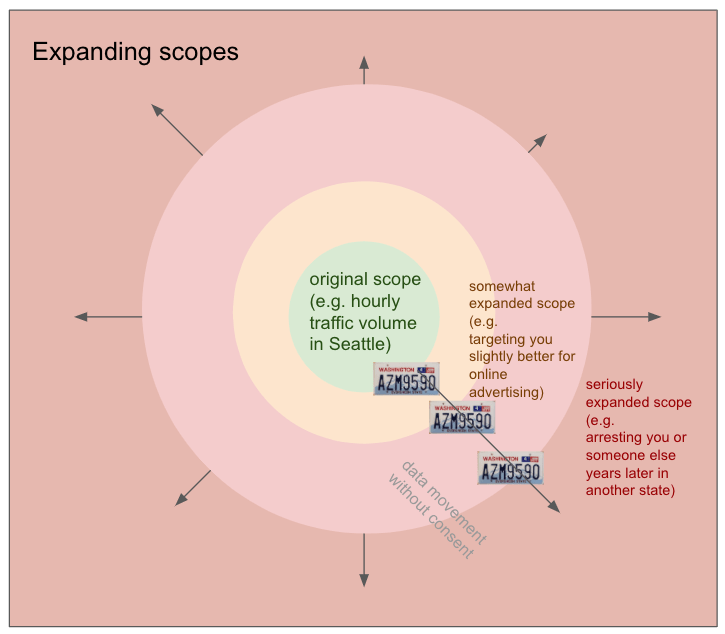

Regulations on ALPR use—both the technology and the data collected—are mostly nonexistent nationally, as well as in Seattle. That means that the agency that owns the system can choose whether and how they want to retain data, or track vehicle movements. Check out the map in Fig. 4: though SDOT says it does not track individual drivers’ movements, data from an ALPR system could easily be combined to do so.

Because of the lack of regulations, nationally, data-sharing is rampant with license plate data. According to EFF, many law enforcement agencies share plate data directly with each other, even across borders. ALPR data also makes it into private databases such as Thomson Reuters’s CLEAR, access to which can be bought by agencies and private corporations. In Seattle, SDOT and SPD say that they do not share data directly from ALPR systems, but it’s unclear what agencies might be able to access data with a request (per the two Seattle Surveillance Ordinance reports on ALPRs).

When it comes to ALPR data, beware of scope creep (Fig. 5): due to pervasive collection and data-sharing, your license plate could leave its original context and purpose and be used in ways you never consented to, such as private investigation or targeted advertising.

How the tech works: ALPR is one of the older surveillance technologies; it was first invented and tested in the UK in 1984 to detect stolen cars. It uses a technique called optical character recognition (OCR), from a field called computer vision, to automatically make a guess at the letters and numbers in a picture of a license plate. This guess is probabilistic; i.e. it could be wrong. Database technologies allow all the information collected by ALPRs to be collected, and questions asked of it.

Interventions

- In 2015, California and Minnesota passed strict laws placing limits on ALPR data-sharing. Minnesota also bars law enforcement from photographing a vehicle’s occupants. (Source: STOP)

Discussion

- Of the three types of ALPRs, which ones do you think should be used in Seattle?

- Is the convenience of travel time estimates (e.g. WSDOT’s chart) or more efficient law enforcement worth the privacy leaks? What are less-invasive ways that we could achieve the same goals?

- How might ALPR use, and data collection, impact you collectively, as an innocent person who is not directly targeted by the state?

Further questions

- What agencies have access to these systems?

- Which cities are using this or considering?

- What are the WA state rules regarding law enforcement using private sources of ALPR data?

- Which tech companies are providing these systems and how much info do they keep (and what is it used for)?

(We are leaving answers to these questions out of our introductory writeup, but encourage you to find out the answers for your city. Thank you to Tech Fairness Coalition members for asking these questions!)

References

- 2018 Surveillance Impact Report — License Plate Readers — Seattle Department of Transportation

- 2018 Surveillance Impact Report — Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR) (Patrol) — Seattle Police Department

- 2018 Surveillance Impact Report — Parking Enforcement Systems (Including ALPR) — Seattle Police Department

- EFF — Automated License Plate Readers

- Automated License Plate Readers & Law Enforcement — 2019

- They Are Watching (ACLU) — Automatic License Plate Reader

- “How ICE Picks Its Targets in the Surveillance Age” (The New York Times, 2019)

- “How Britain Exported Next-Generation Surveillance” — on the invention of ALPRs (James Bridle, Medium, 2013)

- Data Driven: What We Learned (EFF study on ALPR data)

Acyclica

Address: Corners of Spring & 5th and Spring & 4th

Appearance: Flat black circles on top of traffic signal control boxes, which are large, gray or painted metal boxes, typically found at street corners.

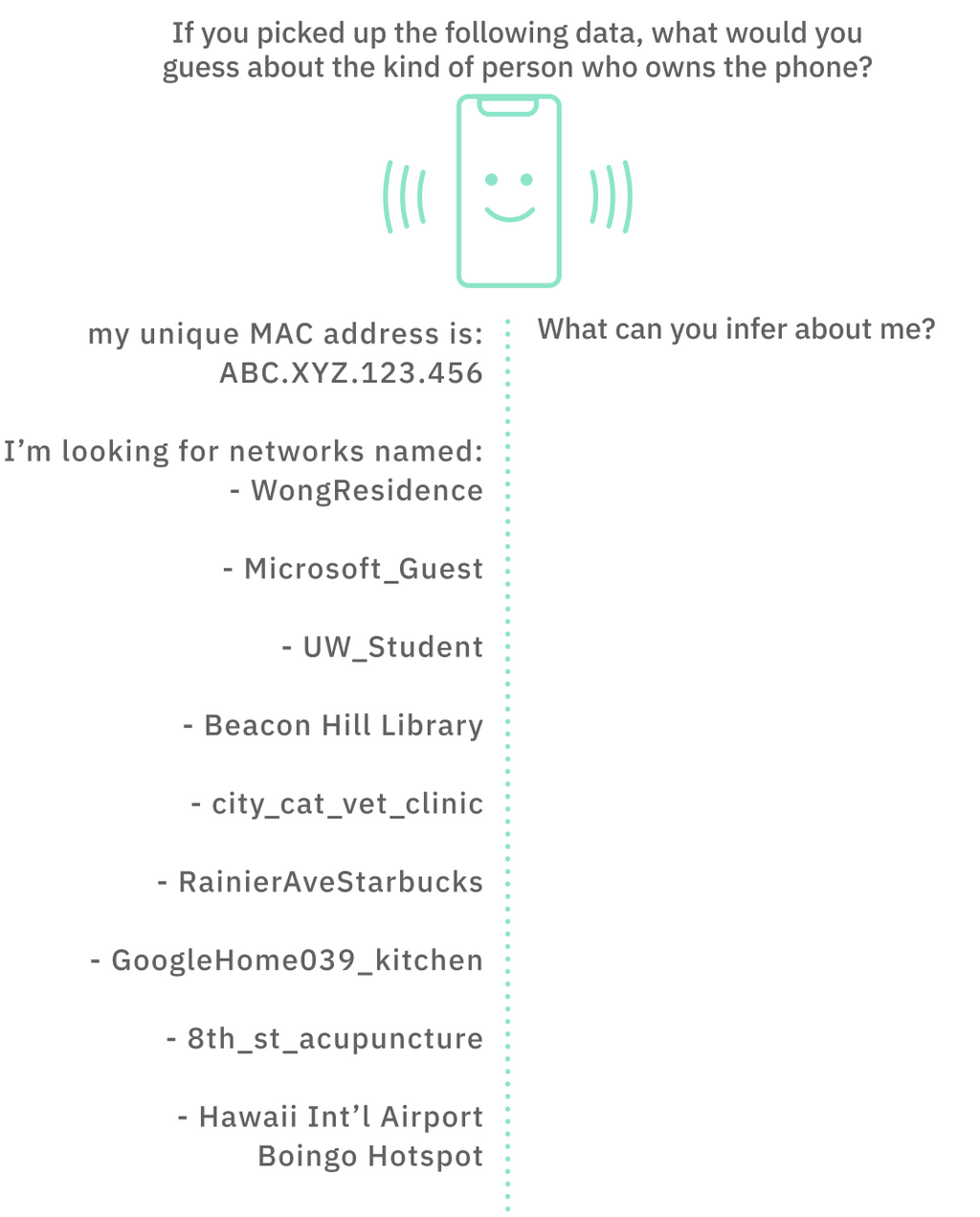

What it does: The Acyclica device casts a fake Wi-Fi network and tracks phones that try to join the network in passing cars. Since each phone has a unique identifier (called a MAC address – like your Social Security Number, but for a device), different Acyclica installations can track your personal location as you pass them in the city.

How the tech works: You know how your phone or laptop auto-connects to Wi-Fi networks? To do this, your device is shouting to the world a ton of your personal information in something called a probe packet. A probe packet contains the MAC address as well as the list of all the past Wi-fi networks that your device has tried to join before, which can reveal a lot about you! (See Fig. 1.) Acyclica listens for these probe packets, and keeps track of the different places it has heard your MAC address to create a location history.

Another big issue is data escaping scope. The Seattle city government may promise certain things about the data, but data that govermnment agencies collect historically has a funny way of being stored for longer than promised and shared with other agencies (like ICE or law enforcement) or quasi-private entities (like Palantir) and used to circumscribe the movements of members of marginalized communities.

Discussion

- How do people feel about how Acyclica is collecting their data? What could go wrong? What does the process of coercive data collection “feel” like a mosquito bite? a highway robbery?

References

- Crosscut news article and overview: Seattle’s new technology tracks how we drive

- Seattle Surveillance dossier (large PDF) on Acyclica (see page 8 for a map of Acyclica locations and page 111 for a bunch of valid technical objections)

- Seattle Department of Transportation overview of Acyclica traffic data collection tool

Washington State Fusion Center

Address: Visit the Washington State Fusion Center (WSFC), in the Abraham Lincoln Building, 1110 3rd Ave, Seattle Washington, 98101

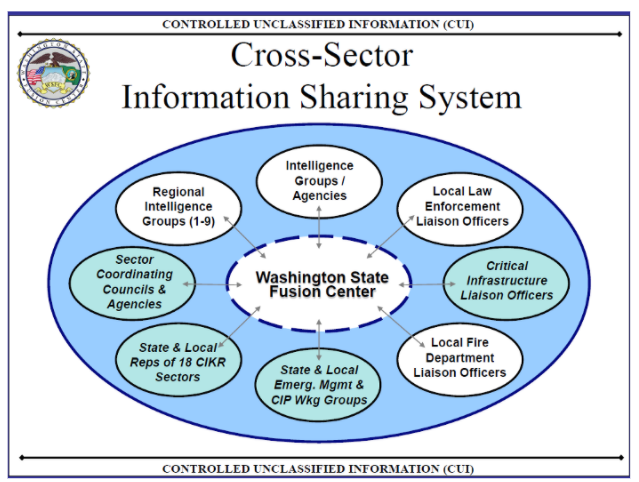

Appearance: Seattle’s fusion center seats a team of 15-30, with full time intelligence officers from the Seattle Police, County Sheriff, state investigators and analysts. These center employees are linked through the State Intelligence Network to every law enforcement agency in the state, and have access to the FBI both through their computer systems as well as through a security corridor linking them to the FBI’s own Field Intelligence Group office on the floor above as well as the Puget Sound Joint Terrorism Task Force.

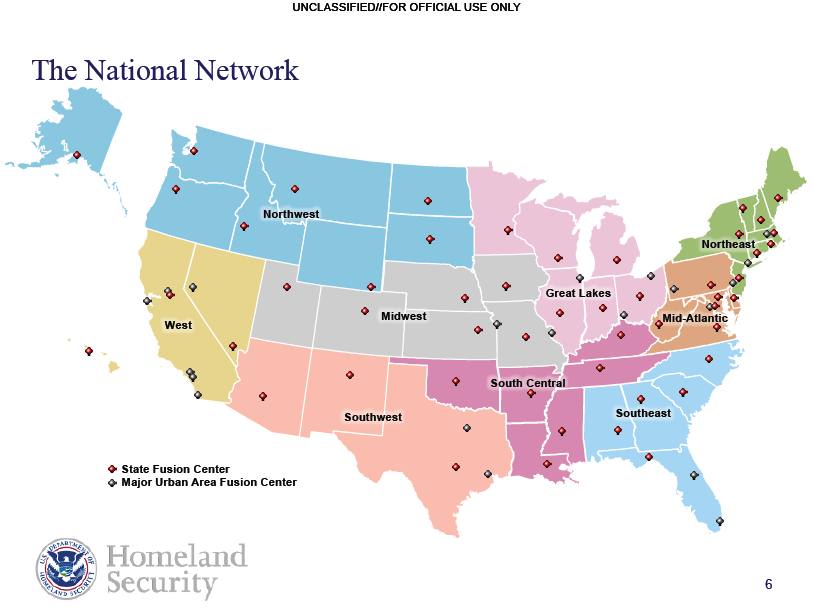

What it does: After 9/11 fusion centers were born with the “Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004” (IRTPA) along with a host of other “counter-terrorism” intelligence entities such as the Department of Homeland Security. With 18 centers first established, there are now 78 recognized centers. Fusion centers facilitated a national anti-terrorism strategy of intel sharing between local and national agencies as well as with private companies and the military.

How to spot: This building’s location in downtown Seattle is no accident. Most fusion centers are typically located in urban centers to put them in the center of multiple agencies that administer public safety needs, fire, emergency response, public health providers, and private sector security agencies.

Multiple incidents of privacy violations and political monitoring are definite examples of concerns associated with fusion centers. But actually as Brendon McQuade argues in “Pacifying the Homeland: Intelligence Fusion and Mass Supervision” this confusing array of coordinating agencies makes it harder to expose political policing the same way as COINTELPRO in the Panther 21 / Handschu Case.

Fusion Centers are mandated to include private sector involvement and their priorities are split between multiple stakeholders at the local, federal, and private level. This puts the role of fusion centers in a fractured light.

Many fusion centers have played a role in monitoring movements. From the Cato Institute’s summary of ACLU Fusion Center reports, “We’re All Terrorists Now:”

“The North Texas Fusion System labeled Muslim lobbyists as a potential threat; a DHS analyst in Wisconsin thought both pro- and anti-abortion activists were worrisome; a Pennsylvania homeland security contractor watched environmental activists, Tea Party groups, and a Second Amendment rally; the Maryland State Police put anti-death penalty and anti-war activists in a federal terrorism database; a fusion center in Missouri thought that all third-party voters and Ron Paul supporters were a threat; and the Department of Homeland Security described half of the American political spectrum as “right wing extremists.”

However, their role during the Occupy movement showed that many fusion centers claimed official policies of non-involvement in line with DHS’s official policies at the federal level. In cases with private sector stakeholder interests such as in Arizona, however, we see a different story. When Occupy Phoenix targeted the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) for its profit ties to ICE and its role in passing a bill that allowed law enforcement to racially profile latinx drivers, Arizona’s fusion center assigns an officer to monitor Occupy Phoenix and liaise with ALEC. ACTIC Provided ALEC with intelligence, including a “persons of interests” list regarding an protest of an ALEC conference who were later targeted with arrests.

How the tech works:

Fusion centers do not store most of the data available to them. Instead, they negotiate agreements that allow remote access to existing databases. They will work around privacy protections and buy access to the private databases (e.g. Vigilant’s ALPR database; see ALPR walking tour stop), which provide a plethora of information on individuals with no criminal record.

Fusion centers have access to the DHS’s Homeland Security Data network, and several FBI data portals. A few databases used by the WSFC include:

- Law Enforcement Information Exchange (LINX)

- FBI Systems

- WAFUSION Intake Log

- Regional Information Sharing System Database (RISS)

- Homeland Security State and Local Intelligence Community

- Law Enforcement Online (LEO)

- Washington State Emergency Management Department

- DHS Infrastructure Protection Protective Security Advisor (LENS, IRIS)

Interventions:

What are tools we have against such a large federal, local, and private conglomerate? The strengths of a fusion center also contain its weaknesses. A fractured chain of command often presents conflicts and confusion with rival agency agendas. It appears that some measure of transparency calls and privacy concerns work after major incidents, with some ability to keep watch on the stakeholder agendas that float through fusion center information requests via public records requests.

Perhaps the greatest effective intervention comes from its funding structure. Though the core “hub” of fusion centers come from federal grants, the specific programs of a fusion center are funded more individually, coming from grants that focus on domains including education, health, and neighborhoods. Such programs promote a model of community wellness that relies on police enforcement. And finally, pre-empting the creation of such centers in the first place might be the most effective intervention with these centers.

Discussion

The location of this fusion center represents a focal point of infrastructure and power. What is being melded together at these fusion centers? Fusion centers popped up in the years after 9/11, particularly from 2003-2007, from an infusion of homeland security grants. This marriage between federal agencies including the CIA, FBI, Homeland Security and other federal bureaus brings a level of national scrutiny to the local level, with individual reporting made possible through the Nationwide Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR) initiative. This resulted in two European businessmen being reported for “looking suspicious” on the Washington State Ferry in 2007.

Seattle’s most famous case involves the arrest of anti-war Port protestor Phil Chinn, a student at Evergreen State College who was arrested during an anti-war protest in May 2007. The activists had been infiltrated by an army intelligence officer who disseminated protestor information through the fusion center. Not long after the Chinn incident, the center changed its name from Washington Joint Analytical Center (WAJAC) to the Washington State Fusion Center and implemented a number of changes that appear to conform to tighter privacy controls and civil liberties concerns from advocates.

Fusion Centers play a large role in a “human rights compliant” world of reformed policing. As Brendon McQuade argues in “Pacifying the Homeland: Intelligence Fusion and Mass Supervision,” the decentralized combination of interests results in a model of “pacification” or control of the economically dis-enfranchised, via a pervasive collection of data to flag and identify locations, communities, and other populations.

We see this in Camden, where a new “reformed” Camden County Police opened a fusion center, the Real Time Tactical Operations Intelligence Center. This center powers a surveillance city, with cameras, ShotSpotter gunshot detectors, automated license plate readers, a mobile observation tower. Community policing interactions become intelligence gathering exercises. All of these data streams flow into Camden’s “fusion center” producing “predictive” analytics to direct police to blocks of interest. Fusion centers exist in a world where surveillance is presented as an alternative model to incarceration and traditional policing. The term used in connection with widespread domestic surveillance – “pacification” – evokes themes of criminalization, gentrification and displacement.

References

- National Network of Fusion Centers Fact Sheet (US Department of Homeland Security site)

- Washington State Fusion Center (official site)

- Washington’s Surveillance Complex (ACLU WA)

- “Watching the Protesters” — on WSFC’s surveillance of Phil Chinn (Seattle Weekly, 2010)

- Pacifying the Homeland: Intelligence Fusion and Mass Supervision (Brendan McQuade)

- Fusion Center Guidelines: Guidelines for Establishing and Operating Fusion Centers at the Local, State, and Federal Levels (US Department of Justice Information Sharing)

- Washington State Fusion Center – Standard Operating Procedures

- Documents on intelligence officer recruitment and training at the Washington State Fusion Center

- 2014 – 2017 National Strategy for the National Network of Fusion Centers

- Fusion Center Guidelines: Law Enforcement Intelligence, Public Safety, and the Private Sector

- INFORMATION-SHARING GUIDEBOOK TRANSPORTATION MANAGEMENT CENTERS, EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTERS, AND FUSION CENTERS

- FUSION CENTER SPOTLIGHT

AT&T peering site (NSA wiretap site)

Address: 1122 3rd Avenue

Appearance: Tall, windowless building tucked behind a bus stop, with an AT&T logo and sculpture on its front.

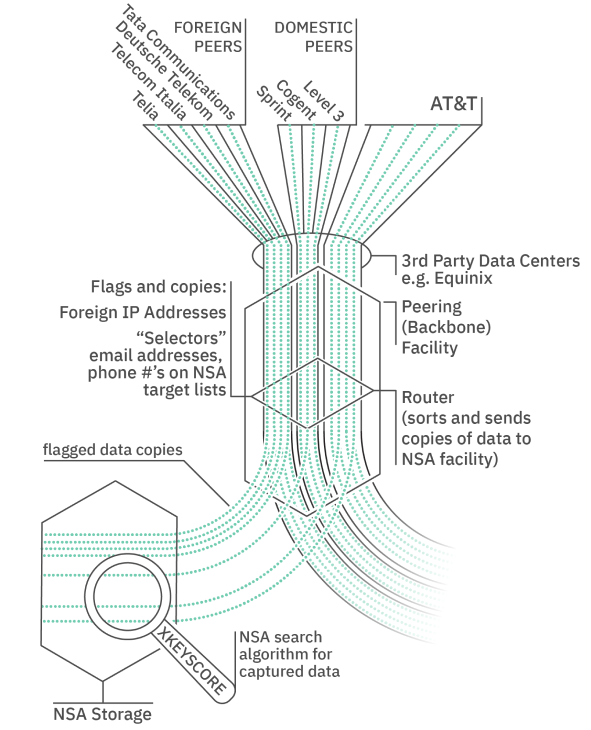

What it does: This is a building called a peering site where telecoms (like AT&T) exchange digital information, such as emails, phone calls, and internet chats. Naturally, as a hotspot of information, this is also a good place for intelligence agencies (like the NSA) to wiretap (or eavesdrop on and record) the information.

How to spot: Peering sites are critically important buildings meant for machines, not people. So, they are usually tall, windowless, shored-up buildings near downtown information hotspots, often near law enforcement or intelligence centers.

How the tech works: Because AT&T has such a huge network, it trades network capacity with other Internet service providers, or exchanges it with them. The way that two networks “peer” is that their infrastructure physically meets in a building (as shown in Fig. 4.) to exchange information.

The NSA is able to eavesdrop on this exchange (through an unknown means) and search through the collected communications.

Discussion

- If you worked at AT&T, what would you do if the NSA asked you to install its wiretapping equipment?

- When it comes to surveillance, should it make a difference whether someone is a US citizen?

References

Discussion

After taking participants through the walking tour, it’s good to bring folks back to a room and have a group discussion of what folks just experienced. Some questions are:

- How can someone “escape the smart city”?

- How is surveillance different in different U.S. cities?

- What are the different layers of surveillance we just discussed? (Help folks distinguish between private, local, state, public, federal, and corporate, and how they interact.)

If you have feedback on this page, or would like to use or adapt the tour in your city, please send us an email.